Hành Tinh Thu Doesn’t Welcome You

Some planets tell you when you're not welcome.

I’ve only been on Hành Tinh Thu for three weeks. I can tell it’s a lot different than Earth. Take my word for it. Don’t plan on going there for vacation or holiday.

Hành Tinh Thu means ‘Collecting Planet’ in the local language, often shortened to Hành Tinh meaning ‘Planet’. It’s in 61 Ursae Majoris, a constellation of Ursa Major, about 31 light years from Earth. It’s a resource planet, minerals and trace elements plus they grow tobacco, tea, coffee and a LOT of rubber trees. It’s been colonized just over a century.

The original native inhabitants, the Bandians, are similar to humans, symmetrically bipedal but generally shorter. The most noticeable physical difference is their eyes, vertically elongated on each side of their thin, hooked, curved noses, like an eagle’s beak. They have a nictitating membrane, a translucent third eyelid. You get the impression of a bird when you’re looking at them. The petite females are kind of cute.

They don’t encourage tourism. I wouldn’t be here myself but there’s a war going on. I’m a mercenary. Born on Earth, in south Texas, my mother was one of those women who put the ‘hard’ in hard-shell-Baptist. I spent three years in the Texas National Guard before I got accepted to the Academy.

In my four years there I was adequate in academic performance, average in military leadership, and above average in physical fitness. I graduated middle of my class. Then I did four tours of duty in Djibouti and Somaliland. I enlisted with the Aiai Order in their war against the People’s Army here on Hành Tinh. West Pointers aren’t well-liked among intergalactic mercenaries, which doesn’t bother me. I didn’t sign up for any popularity contests.

Another major difference between Hành Tinh Thu and Earth is the way it was formed. While Earth is more or less a solid sphere around a dense core, Hành Tinh Thu is more like a round sponge, with plenty of voids and air pockets in it. That can be beneficial for mining but also means the planet is shifting constantly as it consolidates. Earthquakes, sinkholes, and tremors are commonplace.

The Thwok-thwok-thwok of a helicopter announced the arrival of the Census Bureau representative and photographer we’d been waiting for. The technology here on Hành Tinh is several generations behind what I’m accustomed to, but the principle remains the same: do unto others before they do unto you.

They were going to accompany the squad I’d be leading out to Thung Lũng Yên Tĩnh valley to a small hamlet designated V251. In the secure zone, V251 was supposedly friendly to us. I’d never been there. We were slated to perform one of the periodic censuses, an evaluation of the hamlet. It seemed like busy work to me, every six months filling out forms provided by the Aiai Order. There had to be a better way to do it than sending out a squad of soldiers.

Captain Edgewater said, “There’s your bureau men” as the noise became more apparent. He’d given Sergeant Fisher and me our orders and situational briefing. “Get moving,” he dismissed us.

“Yessir,” I acknowledged.

We emerged into the hazy Hành Tinh sunlight. I was lucky to have Fisher with me. He was not only experienced; we’d reached an understanding between us. As a new lieutenant on-planet despite being his commanding officer, I recognized I needed his local knowledge and experience. He acknowledged I was in charge as long as I didn’t do anything stupid. On the single mission we’d been out on, the men took their cues from him. That made sense to me, I was an unproven entity. The silver lieutenant’s bar in my pocket didn’t confer any knowledge at all, just authority.

Squinting against the dust the helicopter kicked up, we walked toward the landing zone. It rotated 90 degrees as it settled down onto the ground; the pitch of the rotor blades and the sound of the motor changed. Two men clambered out. They instinctively hunched over after they exited. One turned back, dragging a couple packs off the floor. The other slapped the fuselage twice. The helicopter immediately rose upward.

“Welcome to Base 60,” I told them, shouting over the noise of the departing helicopter. “I’m Lieutenant Bauer. This is Sergeant Fisher.”

“Conway,” one introduced himself. “This is Danny Zia,” he indicated the photographer.

“Hiya,” Danny Zia said. He wore a tan bush jacket with a multitude of pockets.

“We’re headed to Thung Lũng Yên Tĩnh valley, ” I told them. “You’re with us.” I checked their boots to be certain they were suitable. Conway wore a camouflage uniform blouse without any markings. They were Aiai Census Bureau men. They’d take photographs and do an on-the-spot evaluation and ask additional questions. Civilians.

We set out on foot, in the same order we’d used on our previous mission. John Boy had point. I stopped to think of his real name—Johnson. I followed him with Sergeant Fisher behind me. Sparky, our radio man, with the goofy grin and the slight stutter was next.

I stuck Conway and Zia in behind him. Pham Bin Binah, a Bandian, followed, then Jerry Adelmann and Bristol our weapons specialist. Bristol carried a heavy automatic rifle and ammunition. He was big, tall and black as you can be, a mercenary from Earth, like me. He’d told me, “I’m a black cat, man,” in his low mellow African voice. Reuben Sanders, known as Ruby, brought up the rear.

I told Conway, “I’m not a tour guide. We’re going to a small village designated V251 in the valley of Thung Lũng Yên Tĩnh. I’ve never been there. I’ve only been here a couple weeks, I don’t know anything.”

“Got it,” Conway said. “I do this all the time.”

I sensed Sergeant Fisher approved of my answer. We settled into a ground-eating pace following the red laterite road. The color of the stones and soil comes from the high content of iron and aluminum.

Mostly, we moved along in silence. Ruby had sung, “I don’t belong in the infantry, why oh why did they take me?” Jerry Adelmann immediately sang, “Your mama sent you off to war, ‘cause she don’t want to fight no more,” a Bandian jody, a marching cadence.

I’d never heard it. The guys must've been in pretty good spirits if they were singing.

John Boy halted us with a hand signal when a foot trail intersected with the red dirt road. He looked back at me. I nodded. We left the road heading west. He slipped a long machete from the scabbard on his back. We proceeded down the trail. It’d been improved and was probably heavily travelled. Overhanging branches had been cut and lopped off. There were even some stumps where entire trees had been cut down. The foliage and trees grew thicker and denser the further west we went.

The trail skirted an old sinkhole. It was pretty much a conical depression in the earth, now grown up with foliage. At some point in the past the earth had opened up and swallowed everything, whole trees, shrubs and greenery. You could tell the difference between the old growth and the new, however. It was about 50 meters across and perhaps 30 meters deep.

The deeper we went into the forest, the more sounds we heard. There wasn’t any wind, even so the soft noises of leaves and branches contributed. Little animals, lizards, mice, rats, and other things added to the sounds. Once I heard a louder shriek, perhaps one of the hunting cats.

We’d come about six kilometers when John Boy signaled with his left hand. We stopped. He listened. I looked back on the rest of the squad. They’d remained in place, not bunching up, experienced veterans. John Boy raised his head, sniffing the air. He indicated we should move forward once again. This time he didn’t look back at me. We’d continued another 200 meters when I discerned an unusual noise. I had no idea what it was. We continued.

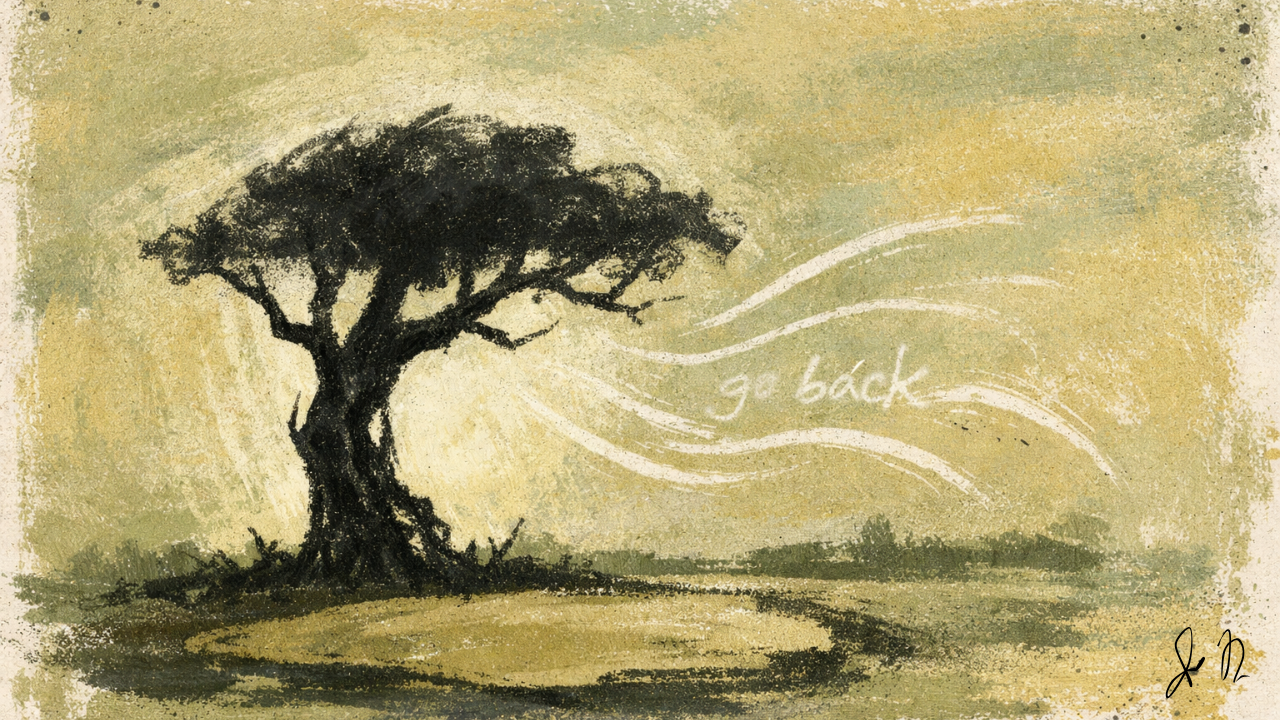

Every 30 seconds or so it was repeated, getting louder. Gabaa! I glanced over my shoulder at Sergeant Fisher. It was apparent he heard it too. Gubaa! He motioned with one forefinger, pointing ahead. John Boy led us further west. Gobaa! The sound continued, louder now. We approached the source and it became clearer. Go baa! The other small forest sounds gradually died away, only the eerie repetition, Go baa! remained.

John Boy came to a full halt, looking back at me; he indicated a tree by pointing toward it with his machete. It looked like a beech tree, multiple limbs spreading outward. Its leafy canopy covered the ground around it. No other trees encroached on its space. It sounded like it was saying, “Go back.” Pretty creepy. I turned to Sergeant Fisher.

“What’s that?”

“A tree. Sounds like it’s telling us to go back”

“What do you think?” I asked him.

“You going to listen to Captain Edgewater or some tree?” He laughed.

I nodded to John Boy and pointed forward. We started moving again, passing the tree, 40 meters to our right. Zia took several photos. I heard his shutter click behind me in the silence. The noise stopped when we passed, even creepier.

Another kilometer further, I said, “Let’s take a break, John Boy.”

He led us a short distance to an opening in the trees. He looked over his shoulder and motioned toward the area with his machete, the unspoken question on his face.

“This will do,” I said. “Let’s take a break, guys.”

John Boy sat down facing west. The rest of the men congregated in a ragged circle except Ruby, who sat facing the direction we’d come. Bristol groaned in pleasure as he set down the heavy automatic rifle and ammo box. Considering the weight of the rifle, the ammunition in the steel case, and the crossed ammunition bandoliers draped over his shoulders, he was carrying 90 or 100 pounds more than the rest of us. He looked grateful for the opportunity to shed that.

Jerry Adelmann lit a cigarette. He carried a pack in his helmet liner. They were less apt to get wet there if we forded any deep rivers or streams.

“Weird tree we passed,” Conway commented. “It sounded like it was saying, 'go back.'”

No one spoke until Bin Binah said, “Minh tree. They make sounds. Some Bandians think they talk.”

“They don’t talk,” Ruby said. “They just make sounds.”

“Some think,” Bin Binah countered.

It seemed to me the good spirits the squad demonstrated earlier had evaporated. I didn’t believe that was due to the presence of the statistician and photographer, I believed the change in mood was due to the Minh tree we’d encountered.

“All right guys, let’s make some tracks,” I told them, ending the break.

We pushed westward in the same order we’d used before, silent John Boy walking point, Ruby trailing behind. The terrain sloped noticeably downward now, as we were entering Thung Lũng Yên Tĩnh valley. This was supposedly secure country, under our control. That didn’t mean the risk of encountering the People’s Army didn’t exist; instead it was negligible. Of course, if you get killed by a booby trap whose existence is negligible, you end up just as dead.

The sun was well up in the sky when we reached the bottom of the valley. The vegetation thinned out along the downward slope. The morning haze had burned off. We were feeling the heat when we came to the river.

I don’t know what its name was, marked as R42 on my map. We used incredibly detailed topographical paper maps. They weren’t 100% accurate but were close to it. Sergeant Fisher told me they erred more often by omission than commission. If it was shown on the maps it was probably there. That didn’t mean that every feature was shown on the maps.

John Boy turned left when we reached the trail alongside the river. We hadn’t gone 50 meters when I heard a distant prolonged scream. Aieeeeeee! It was immediately followed by repetitive sounds, which were hard to describe. If they hadn’t been so loud I’d call them gasps. Ah uh–ah uh–ah uh. They went on for half a minute, gradually getting softer until I couldn’t hear them.

We all stopped. “What the hell was that?” Jerry Adelmann asked. He looked at Sergeant Fisher.

“No idea,” Sergeant Fisher said.

“Maybe a cat?” Ruby spoke.

“Never heard that before, nothing like that.”

“Maybe another Minh tree?”

“I don’t know, man.”

“Is monkey,” Bin Binah said.

“That ain’t no monkey,” Bristol told him. He sounded pretty certain.

“How do you know?” Bin Binah asked him. Bristol was silent.

“Well whatever it was, it was north of here. We’re headed south.” I made up my mind. “Let’s go.”

John Boy led us forward. We resumed our trip to V251. I think everyone was a little edgy, but we didn’t hear it again.

Six more kilometers brought us to V251. It wasn’t much. Bamboo and grass had been the main construction materials over the years. Adobe had been used too, in sparing quantities. There were eight structures I’d call rondels, some lean-tos and bamboo pens. That was it. Zia snapped photos as we entered the village.

Three small children played together in the dirt. One stood up, looked at us solemnly then ran off. The remaining two stayed crouched, looking up at us with their avian eyes.

John Boy halted. Sergeant Fisher told me, “I’ll take it from here,” stepping forward. I followed him. My job was to watch, listen, and learn regarding what happened next.

Bandians seemed to come from everywhere. Most were children. Some were babes in arms, held by mothers or holding their hands or skirts. There were more females than males, females of all ages. The last to arrive was a frail old man, quite short, perhaps 125 centimeters; it was difficult to judge as he was stooped and bent over. He greeted Sergeant Fisher by raising both his arms, holding his hands out to each side and squatting down, bending at the waist and knees. The rest of the inhabitants of the village stood around us in a semi-circle and watched.

Surprisingly, he spoke English. “Welcome, Fisher.”

Sergeant Fisher made a similar gesture, much more gracefully. “Old man, it pleases me to see you so healthy.”

I took the old man’s grimace for a smile. He did not appear to have any teeth. “Not dead yet,” he said. Pham Bin Binah and Sparky moved to either side of Sergeant Fisher. They’d done this before.

“We have questions about your village,” Sergeant Fisher told him.

“Yes,” the ancient Bandian acknowledged.

At that point, they stopped speaking English, continuing in Bandian. Sparky produced the list of official questions we were to get answers to. He read them in English, Bin Binah translated them to Bandian, putting them to the old man. He answered in his native tongue, Bin Binah translated the answers, and Sparky recorded them. Fisher and I listened carefully.

“How many people in the village?”

“31.”

“Are you all healthy?”

“Hoa is with child. It is not easy for her.” Hoa was pushed to the front of the gathering. She shyly displayed her protruding belly. She looked pregnant to me.

The interrogation continued slowly. Sometimes Sergeant Fisher would ask for clarification of an answer. We learned the rice crop had been good; fishing was not as bountiful as it had been last year. The water level in the river was lower this year, so perhaps that had something to do with it. The pigs were fertile and continually had litters. The tobacco was growing. The details went on and on.

Then they came to the subject of the missing boy. Cao, son of Mai had disappeared a week ago. He was 12 years old but tall for his age. It is unlikely that he had joined the People’s Army. They hadn’t been around the village for five months. He probably did not run off to work for the Order—it was known that they don’t accept workers that young—but he was tall for his age. It seemed unlikely he ran away. He was a good boy and had two baby piglets from a recent litter he cared for. They were left alone now, so Mai had to care for them. They asked if we would like to see them, but Sergeant Fisher declined.

“This is a matter of concern,” Fisher said.

“It is so,” the old Bandian agreed.

“Beyond that, it seems your village is well.”

“We try our best.”

Sergeant Fisher told me, “Give him some chocolate and some nicotine gum.” That took me by surprise. I dug into my pack for the field rations. The elder accepted the packages with both hands. He seemed grateful.

“These men will make a record of your village and ask more questions.” He motioned Conway and Zia forward. That seemed fine with the old Bandian. He was unsurprised at least. Bin Binah translated for Conway. Sergeant Fisher turned, walking away.

“That’s it for us,” he told me. “We got what we came for.” I had the men fall out. We waited.

Sergeant Fisher sat down next to me. “That went all right,” he said, “although I’m concerned about the missing boy.”

“It didn’t sound good.”

“It's unlikely he left home intentionally. He’d have told his mother, maybe they’d have consulted with the elder. He’d have sold the pigs or made arrangements for them.”

“You don’t think he ran off to join the People’s Army?” I asked.

“It’s possible. They came through here five months ago and they do recruiting in villages like this one. Trying to sell the idea of Hành Tinh Thu’s resources for the Bandian people rather than for the Aiai Order.”

“Would they tell us if that was the case?” I asked him.

“I like to think so,” Sergeant Fisher said. “I get along pretty well with the old Bandian.”

We were both silent for a while, watching Conway and Bin Binah talk with the village elder. Sparky had a group of fascinated children around him as he demonstrated a yo-yo. Chickens strutted about pecking at the ground. Dogs wandered. The rest of the guys were sacked out on their packs, with their eyes closed.

“I guess the age bothers me,” Sergeant Fisher said. “At 12 years old, it’s unlikely he suffered a fatal accident. By that age he knows his way around, he wouldn’t get lost and probably wasn’t fatally bitten by a poisonous snake or lizard. Doubtful he fell in the river, the kid probably swims like a fish. He’s big enough if he fell in a sinkhole he’d probably be able to get out.”

“12-year-old boys do take risks,” I commented.

Sergeant Fisher nodded agreement. “There’s a sinkhole further downriver that opens up into a system of caves. No telling how far down it goes. He might have been exploring that.”

“That scream we heard. Bristol said that wasn’t a monkey.”

“I don’t know what it was,” Fisher answered.

“It might have been a 12-year-old boy,” I said.

“Be a coincidence if it was,” he replied.

“Back on Earth they train army officers at a place called West Point. On one of the tests they asked a question I got wrong. It went something like, You’re a colonel in charge of the allied force and there are 100 rebel insurgents up a hill. Then they go on to list your resources. You’ve got a 250 man company of soldiers, three tanks, a pair of heavy machine guns, the list goes on and on, mortars, a tactical nuclear weapon, who knows what all? What do you do?” I paused. Sergeant Fisher nodded. “So I worked out an elaborate strategy that’d take the hill, enfilading fire, simultaneous attacks on both flanks, tanks attacking directly up the hill. I was proud of my answer.”

“Yeah?” Sergeant Fisher said. “But you said you got it wrong.”

“I did. The answer they wanted was, You turn to the Captain and order him to take the hill.”

“What’s your point?” he asked me.

“Maybe we should tell the head man about the scream.”

“Ahh,” he replied, obviously thinking about that. He looked at me. “Good idea. I should have thought of it.”

“Well, Sergeant,” I said. “Go ahead.”

We’d concluded our visit to V251. The old Bandian had listened to Sergeant Fisher’s story of the scream we’d heard indicating he’d send two men from the hamlet upriver in the morning to investigate. Sergeant Fisher declined the offer of a chicken. We headed back north on the trail along the river.

By then, the sun sank toward the horizon. Dusk came early in the valley. When we reached the junction with the trail leading back to the road it seemed stopping for the night was the thing to do.

“Pick a good spot for the night, John Boy,” I told him. “I’ll call in and give a sit-rep. We’ll get a good night’s sleep, but let’s get a little further from the river. No telling what’ll come out of there at night.”

We settled on an open area located uphill on the trail. I don’t know what geologic chain-of-events led to its creation, but a roughly circular field of bare earth and sparse vegetation seemed suitable. Unlike most of the area around it, there was a granite outcropping on the uphill side. I didn’t see any reason to set out our tin-cans-on-a-wire perimeter warning. We were in supposedly secure territory. It commanded a good view and field of fire all the way down to the river. With a sentry on top of the granite rock, we'd be safe.

Conway, the civilian, griped about the need to spend the night in the field. I pointed out to him that he and Zia had delayed us. The alternative of making a night march wasn’t strategically necessary, and it wasn’t attractive, either. The guys fell out, doing what they could to make the area more comfortable for sleeping by clearing loose pieces of shale, tossing them downhill. Eventually everyone had a sort of depression they could sleep in.

Sparky unpacked and set up his radio. I called Com Base, reporting our position, affirming we’d completed the V251 reconnaissance. Despite our position, I established a watch schedule. John Boy would take the first segment.

Everyone settled in opening field rations, luxuriating in being off their feet and relaxing. I had stew. I don’t know what kind of meat it was, definitely not beef, but pretty good, dark and rich. It had bok choy and something like snow peas mixed in it. Jerry Adelmann, who’d be sleeping next to me, sat after he ate, lighting a cigarette. Bin Binah and Ruby played some game using wooden counters with beads of different colors they traded back and forth. I couldn’t tell who was winning.

I settled back after eating, took off my helmet, closed my eyes, and drifted off to sleep. It’d been a pretty good day. Everyone was safe.

I was awakened during the night by Sergeant Fisher. He clasped my forearm and squeezed repeatedly. “Something’s up,” he half-whispered.

I came awake fairly fast. “What is it?”

“Listen,” he said. I concentrated, focusing on my hearing. In addition to the normal night sounds I heard an additional noise, similar to pouring something like rice or beans out of a 50 pound bag. Pea gravel maybe. “Sparky says it’s getting louder.”

“Y-y-yeah. B-b-been going on a couple minutes,” Sparky contributed.

Not only was it getting louder, the rate at which the sound was increasing went faster. I rolled over toward Jerry Adelmann. I could make out his form in the pale moonlight, sleeping on his side, turned away from me. I shook his shoulder.

“Jerry, wake up,” I whispered.

“Whussat?” he finally responded.

“Wake up. Wake the guys,” I told him. The noise grew louder. By now whispers couldn’t be heard. I turned toward Sergeant Fisher. “Everybody up,” I told him. Although the noise seemed to be coming from down the hill it grew closer. I realized small runnels of earth and stones were sliding down the hill.

Bin Binah’s voice called out, “Sinkhole!” Then I realized what was happening. The soil, earth and stones, bits of shale, were sliding down the hill toward an opening, like flour through a funnel. The darkness added to the confusion.

“Up the hill!” Sergeant Fisher called out.

“Everybody up the hill!” I echoed him, ordering the squad to climb upward. I could see a dark opening below us into which part of the hillside was rushing. It was eight meters across and rapidly growing larger, obscured but not invisible in the night.

I climbed upward, struggling against the tide of stones and soil. Now the noise sounded like an ocean, a continuous background to the calls and exclamations of the squad. I reached the granite outcropping above us. Now, instead of scrambling on hands and knees, it was necessary to climb.

I stood on the unstable footing, beginning to scale the rock. I wasn’t the only one. I went rapidly, fingers and boots searching blindly for crevices and hand-holds that provided support. Sergeant Fisher was next to me clambering upward. Jerry Adelmann was lower down, having a hard time of it. Conway and Zia were the lowest.

Conway waded upward through the onslaught of earth and rocks. He sank down to his knees in the loose detritus, struggling for each step. I boosted my head and shoulders over the edge of the granite outcropping, kicking and climbing simultaneously. Finally, I got all the way over, turning back, looking downhill over the hard rim of rock. My scramble was more tactile than visual. I’d felt my way up the dark granite face.

Bristol was right behind me. He’d carried his automatic rifle and ammo box up the hill through the landslide but couldn’t climb the face of the rock with them. I reached down for the gun. He extended his arms, passing it to me. Sergeant Fisher came over the lip, kicking with his legs to boost himself up. Bristol passed me the heavy ammo box next, starting his climb up the face.

By now all I heard was a dull roar as tons of loose material slid down the hillside into the dark maw of the hole. Jerry Adelmann clambered over the verge of the rock, collapsing on his face, gasping for air. Ruby had his rifle slung over his shoulder and his pack on his back. He’d even donned his helmet. He made his way up the steep granite rock slowly. I hadn’t seen Bin Binah until he came up behind me. He must have been one of the first to make it to the apparent safety of the rock.

Zia, sans camera and other gear, helped Conway to the base of the granite. By now it was a higher climb than it had been when I’d ascended. The cascading stones and soil had unearthed portions of the rock which hadn’t seen the light of day for who knows how long. Maybe never. They were the last to make the climb.

Sergeant Fisher and I looked at one another. The whole squad had escaped the sinkhole. It appeared to be slowing down. The noise, too, lessened.

“We better get off this rock” Fisher said. “If it goes, I don’t want to be here.”

I agreed. We directed the men upward, stopping 100 meters higher up the valley where we regrouped. I counted everyone. I was amazed we’d all survived.

We took stock of what weapons and supplies we had and what we’d lost. I had my pistol but lost my pack and rifle. I don’t remember putting it on, but I wore my helmet too. Sparky was fully equipped. He’d been pulling guard and sentry duty when it had started.

John Boy was another one who’d saved all his gear including his machete in its scabbard over his back. Bristol had amazingly made the climb with the precious automatic rifle as well as his carbine and all of the ammunition except for one bandolier of .50 caliber bullets. Ruby appeared fully equipped. Zia and Conway had only been able to save themselves. Conway was lucky that he’d done that. I don’t think he’d have escaped if it hadn’t been for Zia’s help.

We huddled there in awe at what we’d experienced.

As daylight broke and the pre-dawn light came into the valley, Sergeant Fisher and I walked down the hill to stand on the huge granite rock and look down at the sinkhole that now filled the area where we’d camped last night. It was about 70 meters wide and had the shape of a funnel, more or less. The hole in the middle yawned deep and black. We couldn’t see the bottom, at least from where we were standing.

“You want to go down there and look inside?” he asked me.

“No,” I told him, shaking my head. “Not in any way, shape or form.”

“Didn’t think so,” he agreed. “We lost the radio.”

“The radio and a lot of other gear,” I said.

“No men, though”

“Yeah, we were lucky,” I told him. “Helluva thing.”

“Yeah, helluva thing. Let’s go home.”

Editor's Notes:

Jon Negroni here, co-editor of this piece along with Natalia Emmons. This is our first time featuring C. Inanen on Cetera, and there are a few reasons why the submission stuck out to us.

At its core, this is a military SF frontier story that blends Vietnam War themes with speculative fiction. It employs colonial occupation narratives and the realism of a "hostile planet" in lieu of a space opera.

The planet itself could've easily fallen into the trap of being an overwritten metaphorical playground about zero inches deep. But instead, it comes off as logistical, dangerous, indifferent, and structurally unstable. That matters because the real antagonist here is the environment itself, amplified by bureaucracy and human arrogance.

In other words, I would put this closer to The Things They Carried than Starship Troopers, if that makes sense.

I particularly enjoy how the narrator is observational rather than poetic. He's not trying to be likable, he just gets hierarchy and procedure and the boredom of it all. He understands that rank doesn't equate to wisdom, which pays off later when he defers to Fisher and ultimately survives by listening.

As with most stories for the magazine, I did the illustration myself using Procreate. I had a few artwork concepts to choose from, and ultimately I landed on the Minh tree being the anchor of the story instead of the climactic sinkhole. The tree itself is so ambiguous. Is it biological? Cultural? Spiritual? All of the above, none of it? Part of my criteria for accepting submissions to the magazine is trying to think of the reader discussion afterward. What would people talk about if they read the story together? And the tree is the most keen discussion point to me in that regard.

And on that note, I'll offer my own theory on what this story is really about. To me it's about false control. In a world where the powers that be think knowledge equals mastery and military presence equals stability, Hánh Tinh Thu does not care. The planet collapses literally beneath them without malice or intent. Even the missing boy is left unresolved, reinforcing the idea that not all losses are narratively meaningful. —Jon Negroni

C. Inanen lives in the Midwest, USA. His work has been most recently published in Yellow Mama magazine. It will also be featured in the March 2026 issue of Close to the Bone, the June 2026 issue of Down in the Dirt magazine, and broadcast January 2026 on YouTube by Antimatter Dreams. He is a contributor to The Yard: Crime Blog.

Support Cetera

Paid members get exclusive perks like bonus stories, the ability to comment, and more. Plus you'd be helping us keep the bills paid. You can check out the subscription tiers below, or you can leave a one-time tip if that works better for you.