The Big Black Square

In every reflection, I saw a happier version of myself—and I finally understood why.

Derrick worked in the big, black square at the top of the hill. Where the sycamore grove used to be, they’d put up an all-black building: a massive, dark cube with featureless sides. I often asked Derrick what he did inside the square, and he’d brush me off. He’d moan about work or change the subject. I never got a straight answer out of him. It wasn’t satisfying: the not knowing.

I’m not even sure why people started calling it the big, black square.

“It’s a cube! A cube!”

But Mom and Dad shrugged me off.

“Kay, you’re thinking about this too much.”

“Cube. Square. Same difference.”

I suppose folks called it a square because, at any given time, when you looked at that huge building, you could see only one face. From a certain vantage point, there should have been a place where two sides met, allowing you to see an edge. But I’d never figured out where to stand to see a corner. So I called it a square, too, even though I knew it was really a cube.

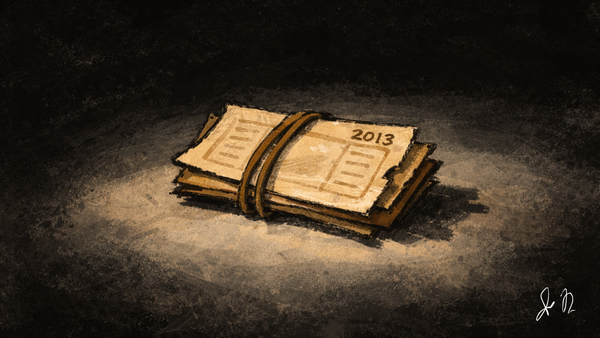

On my first date with Derrick, I don’t recall if the fact that he worked inside the square at the top of the hill even came up. We spent most of the time talking about sitcoms we watched in the early 2010s. How it took us both a couple of watches to get into Community. I mentioned how I’d moved across the country so many times, shifting between different branches to manage, then being a regional coordinator. He mainly explained the arcade cabinet he was building in his garage.

They must have built the big, black square sometime before I got sick and moved back home. When it was too expensive to fly up from Miami. I never appreciated how much more costly it was for my parents to buy two tickets to fly down than it was for me to buy one. Sometimes, even when you’re thirty years old, you’re still a little kid with money and your parents and all that jazz.

Being back, one of the first things I noticed—well, after the big, black square—was that everyone waved to me. I assumed it was because I’d been away so long, and people were glad to see me again. Even if the reason I was back wasn’t so great. No one waved in Miami. Everyone was always in their cars, and even in the townhouse complex where I lived, folks didn’t wave. So the waves in my hometown were nice.

When we first started dating, Derrick used to be a lot more, let’s say “nice,” too. He would offer to pick me up and pay for things. Then it was all complaints, complaints, complaints.

“They’re not paying us enough.” “I can’t even buy gas.” “They promised us raises, and now they aren’t even paying overtime.”

I chalked it up to capitalism and corporate greed. The more I thought about it, though, there were things that Derrick used to do when we first got together that didn’t cost a dime. Asking how my day had been. Telling me an outfit looked good. Noticing if my mood was down, and maybe I needed to snuggle. Also, later on, there were things Derrick did for himself that did cost money—mostly putting parts into his arcade cabinet.

I’d argue it’s fair to start thinking about the capitalism angle, and then wanna know who owned the big, black square. Maybe it was underwritten by the government or the military. My mind started seriously running itself ragged as I thought about it more.

“Mom, who even owns the square?”

“Oh, hun, please, we already went through all of this during the meetings with the town council.”

“Okay, but I wasn’t there, Mom.”

“Don’t get mad at your mom, bear. She’s just telling you what happened when you weren’t here.”

“But she isn’t, Dad. She’s talking around it.”

Those discussions usually turned into me yelling at one of them, tearing up, and running to my room. I felt sixteen again.

Derrick’s tones were a lot slicker than my parents’, but the contents of his obfuscations were pretty pathetic. I’d ask him who paid him or what he’d even put on his resume.

“I know who writes my paychecks, okay. Now watch this drive.”

Then he madly swung at the golf ball, and it wasn’t even impressive. He didn’t rent me a bay at the driving range, because “they still haven’t paid me for that extra weekend shift.” Okay, but offer me a swing or two, Derrick.

My old high school friend, Ashley, wouldn’t come back in town anymore with the square around.

“You can stay there if you want, but that thing gives me the fucking creeps, Kay.”

Ashley lived right outside the town limits and thought there was a magic line where, if you were beyond it, then the square wouldn’t “get you.”

I suppose she was right to be wary. I remember every annoying step that time I went to surprise Derrick and see if he wanted to grab dinner after work. I walked and walked and walked around that stupid cube—and it was definitely a cube, because I had to pace all four faces looking for an entrance or door or anything. It took five minutes to scour each blank side. I kept pausing to find a corner, but I must have missed where to stand, even up close.

I huffed back down the hillside, scanning around for a porthole, bunker, or side entrance. Nothing. Nada. Just hill and some litter. A sun-faded umbrella with a pizza chain logo on it, flipped upside down, with an ice cream cone desiccating inside. Some critter licked out the soft serve but left the cone part.

“Why were you trying to come inside?!”

“I wanted to take you out to dinner, dummy.”

“Don’t ever fucking go there.”

“Okay. Okay. Okay. Sorry.”

If I’d had the mental bandwidth, I’d have noticed the change in Derrick more. Frankly, I didn’t have the energy to deal with him sometimes. It took me most of the day to get to the hospital in the next town over, get treatment, probably wait at the pharmacy to pick up meds, and then get home. I should have been more mindful, but I wasn’t.

Dad was the first to notice the change in my mood. I’d been getting snippy with my parents.

“You sure the treatment isn’t taking too much a toll, honey bear?”

“Yeah. It’s working for the most part. It’s just a lot of driving, I think.”

Little things piled up and ate away at my patience, turning me into kind of a recluse. I hadn’t visited Ashley in months by the time she called and begged me to come see her.

“You seem really different, Kay.”

“The doctors say it’s the course of progress, you know?”

“No. That’s not it. Like, can you see yourself, I mean?”

“What a question. Yes.”

“Go look in the mirror.”

“I don’t know what you’re getting at….”

“Kay, look in the fucking mirror!”

I stormed out of her house. I’m sorry, but I don’t need more people being mean to me. It’s pretty clear that Ashley and I had drifted apart. When you’re dealing with a big medical thing, it shows you how people see you. Ashley was right to be concerned, but you shouldn’t yell at someone like that. It’s infantilizing.

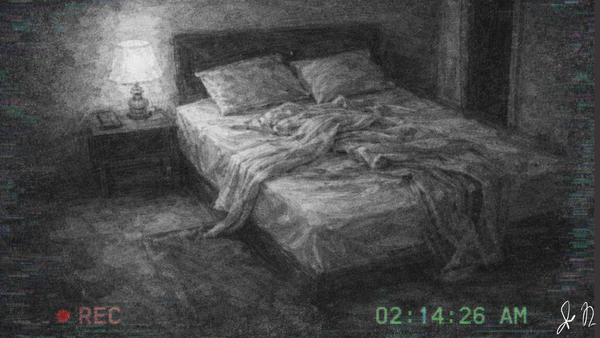

Derrick wasn’t answering his phone that whole weekend, and Mom and Dad were doing something, and I was stuck at home watching reruns of 30 Rock. I knew Ashley was noticing something, and I didn’t want to admit it, so I snuggled under a gravity blanket and didn’t look in the mirror. But every so often, when the screen went black where commercial breaks would be, I’d catch a glimpse of myself in the TV. Or rather, I’d catch a glimpse of someone. She looked like me. Same thinning hair, same shape. But she was always so much happier than I was. It’s not like she had a big, stupid smile stuck on her face. Or really, that I could even see her face. You know how you can just tell someone is content? Like their life just works? That was her. That was the woman I saw in the TV before Tina Fey appeared in the next scene.

People used to talk, when I first got back in town, that there would be a renaissance because of the big, black square. The town got different after a while, but it wasn’t better. Everyone seemed mad and drove like crazy. People had stopped waving to me, too, but I thought it was because my being home wasn’t new anymore. I remember feeling like I was back in Miami—what with the no waves plus the scary driving.

Like this one time, I was late to meet Derrick at this wine bar, and I kept circling for parking. Some old lady in a beat-up SUV was following me super close. I didn’t think anything of it, because maybe we both needed to park in the same block. A car pulled out of a spot ahead of me. I swear to God, this old lady gunned it around me so fast I could have died! She crammed herself into that spot lightning quick. Once the shock wore off, she leapt out of her car and berated me.

“How dare you!! You know I always park here. This is my spot!”

That old woman marched up to my car and kicked the headlight so hard it shook the whole vehicle. She didn’t break the light, but she probably broke her foot, because she hobbled away screaming and swearing at no one in particular.

I was so late by the time I found a parking spot. Derrick had left and given a nasty note for me to the hostess, whose eyes shot daggers. Like she even knew me.

It was probably around then when the doctors stopped the treatments and gave me a referral to the big clinic across the state line. It all happened in the portal. If I hadn’t checked the message, I’d’ve driven all the way to the hospital in the next town over for nothing. I called my nurse practitioner, who didn’t even want me to come for a final visit.

“No, no. It’s okay. Don’t come in. We all said it’s okay you don’t come in again. You should probably consider getting an extended-stay by the clinic or something. To, um, stay near there. Get away from home for a bit. Outta town. It’s probably a pain to drive so much, huh?”

It was, but packing up and moving to a hotel for a couple of months wasn’t ideal either.

I told Derrick about the referral, and he basically threatened to break up with me if I left. He said he didn’t have time to drive there or wait around for me to finish my treatment and come back. That almost made me not go.

That same day, I was getting a haircut—well, my wig styled would be more accurate. But I still called it a haircut and thought about it that way, because it was more normal. I was sitting in the chair, and the hairdresser was talking about how much she couldn’t stand her college friends and how they all went on vacation without her. I asked to see the back of my hair, twirl me around and hold a mirror so I could see the mirror in the mirror sort of thing. She looked at me like I had snakes for hair.

“We’re done here. You look good. Don’t you question me. I did what you asked. Now go!”

It was so awkward trying to tap my card on the pay-thingy, and the hairdresser was almost growling at me. Then I caught a glimpse of my reflection in the shop’s window. I looked radiant. Angelic. Whoever this woman was, she got a truly dope haircut. She wasn’t dejected in her hometown. Or sick. I wished I could be her for five minutes.

That whole thing made me want to finish getting better faster. So I pulled enough money out of my savings to stay at the hotel. Mom and Dad begged me to stay home. It took a few weeks, but the big clinic did get me in. That whole time, I roosted at home and rewatched The Office. Derrick mostly ignored me. Except he sent two pics of himself out at some bonfire. He looked blissed out of his gourd on MDMA or ecstasy or something. Psychotically happy. The Derrick I’d gotten used to was surly and always hated something. This beatific Derrick wasn’t the one I first met or knew now. It turned me off fast.

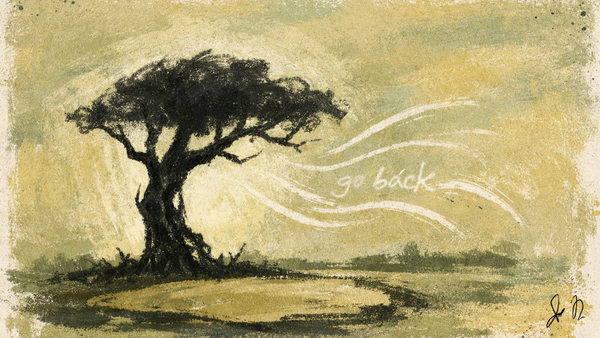

I left town and drove out, and the big, black square was the last thing I saw. I swear there was a single window near the top. A tiny indent in the empty side. It’s not like I was close enough to see into it, but I’m sure I saw a silhouette of a person. I imagined it was Derrick up there in that window watching me go, so sad he wasn’t nicer to me.

I lived in that extended-stay hotel for the next few months. They had a shuttle that picked me up because parking at the clinic was a pain. It was kind of fun but also sad, because there was this little girl and her mom who rode in the shuttle, too. They never said anything to me and stayed at the back of the bus. Sometimes the little girl waved at me if I smiled at her once the shuttle started moving. It felt nice to get waved at again. I didn’t know what the girl was being treated for, but she always sang little songs with her mom in this silly call-and-response way.

“Going to the hospital.”

“Going to the hospital.”

“To get the medicine.”

“To get the medicine.”

“She’s gonna be real brave again.”

“She’s super gonna be real brave.”

“The doctors are her friends.”

“Doctors are her friends.”

I holed up in the hotel room when I wasn’t at the clinic. I put the air conditioning down real low and watched a lot of cooking and house-hunting shows. It felt good because, unlike my sitcoms, I didn’t know what was gonna happen in the shows. Maybe they’d go with the house that had the big backyard, or the chef from the food truck would win the dessert round.

The whole time I was getting the treatment at the clinic, Derrick didn’t call or text once, and I was almost certain we were broken up. Dad called a bunch at first. But he only wanted to talk about a big project he’d started: installing a beer tap line in the basement. I thought it sounded cool at first. Except he didn’t stop telling me about it, and I asked about Mom, and he kept blabbing about the tap line. He would interrupt my updates about the treatment and say it was “boring and sad” to hear about me being sick, which was true in some way, I suppose. It reminded me of those times with Derrick, where I would tell him it had been a bad day at the hospital, but he would yammer about his arcade cabinet in the garage. All those men had these little projects, and you had to hear about them and ask questions, or they’d sulk.

I must have pushed Dad too hard about Mom, because he snapped one day.

“I am trying to—so hard—to make a nice basement bar for you and your mother, bear. And you two won’t support me. Just leeches!”

I didn’t speak with him for the final weeks at the big clinic. Mom never answered her phone or returned my messages, and I almost called the police. But I figured I’d wait until I came home, in case maybe she was scared for me and talking made it worse. So, I had no idea what it was like back home.

I got better and better, and I think that little girl did, too, because the last time I saw her, she was able to run up and down the shuttle bus aisle pretty fast. Way faster than she could a few months before. The big clinic told me to check in with my usual doctors; they sent me off with a stack of papers and a thumb drive, but they said all the details would be in the portal.

I tried to call my nurse practitioner at the hospital, a town over from my hometown. The selections looped and looped through the automated system. So I drove there to speak to someone in person. The hospital was basically on the way from the big clinic back to my parents’ anyway.

The town with the hospital was so dangerous! There were scary drivers, and everyone was honking as soon as the light turned green if I didn’t floor it. I saw two gruesome accidents because cars were driving way too fast. When I got to the hospital turn-off, I didn’t have to guess why the phone wasn’t connecting to anyone. There was a big, black square where the hospital used to be. It was a massive black cube, identical to the one in my hometown. Every time I could look away from the road, I only saw one side of it. I was tempted to get out and ask someone when the hospital closed and the square got built. But I was sure they wouldn’t even tell me the time of day, given how rushed and frantic they all were.

Instead, I kept driving. If my old doctors had a new office, I figured the big clinic had sent them the right stuff the right way. I was planning to go straight back to my hometown when I got a notification from Ashley. It was a voice memo, and I played it after I got far enough away from the wacky drivers.

“Kay, you bitch. I can’t stand you. I hope your insides rot, you fucking cunt.”

That wasn’t like Ashley at all, but like I said, she and I had drifted apart. In that moment, when I was looking in the rearview mirror to make sure no bad drivers were around, I realized how I looked more like myself again. Much sadder than that lady I saw in the TV blackness or the hairdresser’s window, but happier than the me I lived as before I was at the big clinic. Does that make sense? Like maybe I was becoming that happy woman I saw in reflections, or she had become more normal and sad. I don’t know.

When I was on the wide county road, there weren’t any tractor-trailers, which was weird. But I liked that I didn’t have to worry about when they’d get side by side and drive a tad faster than the speed limit. I was making such good time that I considered stopping to see what was wrong with Ashley. Maybe I’d have to apologize in person if we didn’t want to stop being friends altogether. I was gonna take the exit to the area where she lived, but the off-ramp was demolished. There were construction vehicles on fire instead, and fat carrion birds circled the scene. There was no other exit, so I had no idea how to get there, except by turning back and exiting in the town with the hospital. No thanks, too many bad drivers.

So I drove back to my hometown.

I could tell where the county maintenance ended, and the town was supposed to take care of the road, because there was all kinds of debris. I bounced all around; it really hurt because I was still healing from the treatment at the big clinic. One of my tires must have popped or blown, because the car started making a ding-ding-ding sound. I pulled over at the old mini mart at the outskirts of town. I remember Ashley and I tried to swipe chewing tobacco there when we were sixteen and got caught. So I hid in the car when my parents stopped there—until right now.

I figured I’d get a water and call a tow truck. I could see inside the mini mart that they’d moved everything to be lined up against the store walls. I opened the door to go in, then had to crawl around a chip rack. In the middle of the store, someone had created an honest-to-God roller hockey rink. It was too little, but it looked like a legit rink you’d see at a park or something. Two mean-looking teens had hockey sticks and were bashing each other in fast blows. One had blood rushing down his face, and the other was missing part of his ear and looked like his elbow was dislocated.

“Who do you think you are?!”

“We built it; you can’t use!!”

The boys yelled at the same time, so I’m not totally sure that’s what they said. It’s close enough.

I ran, and those two boys hoofed it after me. When I looked back for a second, I could see them mirrored in the mini mart window. Those two reflections seemed so happy, so serene. I wished it were those boys who were chasing me instead.

After the two boys beat my legs and arms, and part of my skull was fractured so that I couldn’t think well anymore, a lot of things made more sense. I believe Derrick may not have ended up being a good boyfriend. So it was probably fine that we broke up, even though I didn’t know if we officially did. I wondered if everything would have been different if I had visited my parents more often while I was in Miami. I bet the problem is that I was away for too long. Maybe that was the problem with me being at the big clinic, too. I wasn’t there to see what was happening, and the world moved on without me.

I slumped on my side, bleeding, and my wig was falling off. Partly because of the blows from the mini-mart boys, but also because my real hair was coming back. I’d gotten used to not wearing a wig grip, so the wig slid more easily now with my own hair regrowing. Too many things had changed since I’d come back home, and I couldn’t adjust quickly enough. I’d concentrated on feeling better—not learning about wig care. Even if I had a wig grip, I’d still be lying in a ditch off the county road, but at least my hairline would have looked nice.

My vision blurred, but I could see enough to notice the big, black square on the hill. At last, I could see a corner where two sides met. It was definitely a cube. That made me feel vindicated, but very lonely. There were hundreds of windows along each side of the building now. And every one of them was open. Inside each one, I’m sure I saw a smiling person. Truly smiling. Beaming. Waving at me. Waving goodbye to me.

Author's Notes

I let my parents read a draft of this piece—an act I reconsidered almost immediately. “Hey. So what’s with the big, black square?” my mom asked, literally the instant we sat down for Chinese food. “Well, what did you think it was?” I replied. I don’t think they appreciated that answer. The fried turnip cakes were good, though.

Before I started this piece, I was stymied by a daunting section of the novel I was writing. Also, I was trapped in my basement for most of the daytime for a week. A single glass block window, my wife, and a frightened dog provided my only light. The walls quaked as cataclysmic scraping thundered around us—contractors waterproofing our basement. In between pets to reassure our sad dog, who huddled on her blanket, the first draft of this piece flowed out of me. I embodied a sparser, more unadorned style than usual. The entire experience felt unhoming.

The idea had nudged at me, of a town where they let someone build a monolith whose purpose was entirely unclear. Not simply allow—celebrate it, operate it. Any attempt to probe further is met with a casual shrug or an inability to talk frankly. As everything grows worse, the notion arises that there’s something wrong with you for questioning anything. Justifications. And even as it spreads, you still have to attend to the simple moments of living. Perhaps, in a different lifetime, Kay would have stayed away from home longer.

Kasey Soska is a professional science nerd and novice fiction writer. His PhD in developmental psychology is from New York University. His academic research has appeared in Developmental Science and Child Development. Kasey studied comedy at Second City’s Conservatory and performed sketch and improv shows in Chicago, Miami, and NYC. He returned to his hometown of Pittsburgh, where he lives with his three-legged dog and two-legged wife.

Support Cetera

Paid members get exclusive perks like bonus stories, the ability to comment, and more. Plus you'd be helping us keep the bills paid. You can check out the subscription tiers below, or you can leave a one-time tip if that works better for you.