The Pomegranate Man

The pomegranate split in his hands—reluctantly, then all at once—and Riam set half of it on the flat rock where the tide would find it by morning. The seeds shone like wet garnets in the last grey light. Forty years he had done this. Forty winters watching the fruit go soft, then vanish, taken by gulls or current or something he preferred not to know.

He climbed back up the path to the lighthouse, his knees aching in the way that meant rain. The storm had been building all day, the sky unduly weighted, and now the first drops struck the windows with the sound of fingernails. He lit the lamp. He put the kettle on. He did not think about Teyo. Teyo was simply there, the way salt was in the air, the way damp was in the stones.

A knock came just after dark.

Riam stood in the kitchen with a cup gone cold in his hands. No one came to the lighthouse in winter. No one came in storms. The road washed out in weather half this bad, and the fishing boats had been hauled up since October. He set the cup down and did not move.

The knock came again, patient and unhurried.

He crossed to the door and opened it. The man on the threshold was barefoot. That was the first thing Riam saw—bare feet on the frozen stone, pale and wrinkled. The second thing was the page in his hand, sodden and falling apart. Riam knew it. He had written it yesterday. He wrote one every year on the anniversary. Had folded it into the rocks beside the pomegranate, weighted it with a stone. If you're real, it said, in his own cramped hand, take something else from me.

The man held it out like an offering. Rain ran down his face, plastered dark hair to his temples, dripped from the hem of a coat that looked a century old. His skin had an undertone that should not have been there—grey-green, sea glass, something left too long in brine. But his eyes were human. Brown and steady and fixed on Riam with an empty expression.

"You wrote to me," the man said. His voice was low, water-smoothed, with an accent Riam didn’t recognize. "You wrote many letters, in fact. I thought it was time I answered."

Riam gripped the doorframe. The wind shoved past him into the house, bringing the smell of kelp, and something else beneath it—pomegranate, sweet and faintly rotten. The man was young. Thirty, perhaps. But his eyes were elder. His eyes had a quality Riam had seen in photographs of soldiers, not long after the wars.

"Who are you?"

The man smiled. There was something wrong with his teeth. Too many, or too sharp, Riam could not tell in the dark. Barnacles clung to the collar of his coat. His fingernails were the iridescent grey of mussel shells.

"You know who I am," the man said. "You've been writing to me for forty years."

The rain was soaking Riam's shirt. His hand was still on the doorframe, the wood cold and slick under his palm. He wished he could close the door. Go back to the kettle and the lamp and the slow erosion of his remaining years. But he could only step aside.

"Come in," he said.

The man crossed the threshold. He left no wet footprints on the floor.

“My name,” he finally said, “is Oannes.”

Riam put the kettle back on. The body knew what the mind could not. How to answer doors, accept casseroles, pretend the world made sense. He had done this before. He found a towel and offered it. Oannes took it but did not use it. Held it in his lap, water pooling on the kitchen chair.

"You're cold," Riam said.

"I don't feel cold." Oannes tilted his head, watching Riam move about the kitchen. "Not anymore. Not for a long time, actually."

Riam put bread on the table, and cheese, and the other half of the pomegranate. His hands were trembling, which he hated. He hated the body's betrayals. Oannes looked at the fruit for a moment, then up at Riam.

"You remembered," he said.

"Oh? Remembered what?"

"The old courtesies. Fruit for the traveler. Bread and salt." Oannes picked up the pomegranate, turned it in his hands. "Most people have forgotten. They leave plastic flowers on graves now, or nothing at all. They don't understand that the dead are hungry."

The kettle screamed. Riam poured water over tea leaves, the motions steadying him, and sat down across from Oannes. The fire crackled. Rain lashed the windows. Oannes's hands rested on the table—the webbing between his fingers barely visible, translucent as a jellyfish.

"You're not going to ask me what I am," Oannes said.

"Would you tell me the truth if I did?”

"I don't know anymore what the truth is." Oannes broke open the pomegranate. The seeds spilled across the table, red and scattered, impossible to gather. "I've been so many things. Worn so many names. But I remember you, Riam. I remember you before you had grey in your hair."

"You couldn't. I was—"

"Twenty-two. The summer Teyo brought you to the cove." Oannes ate a pomegranate seed, his lips staining red. "You were afraid of the water. You sat on the rocks while he swam out past the breakers, and you watched him like he was the only bright thing in the world."

The room tilted. Riam pressed his palms flat against the table. He had not spoken of Teyo to anyone in years. There was no one left who had known him before he became the old man in the lighthouse, the keeper whom the village children dared each other to visit.

"He talked of you," Oannes said. "After. At first he talked about you all the time. In fact, your name was the first human word I learned from him. Then, as time passed, he spoke of you less. Then not at all. Time moves differently, down there. Memory goes soft. Like fruit in water."

"After." Riam heard his own voice as if from a great distance. "You mean after he drowned."

"I mean after he became what I am."

The fire popped. Sparks rose and died. Riam looked at Oannes and saw the inhuman creature beneath the human mask. The way his chest did not rise and fall with breath. The faint glow of his skin in the dim light. The absolute stillness of him, like the moment before a wave crashes shore.

“That's obviously impossible," Riam said. He said it to the table, to the scattered seeds.

“Nevertheless, you've been writing to me for forty years. You've been leaving fruit for someone you don't believe in. Why?"

"Because…”

“Because what?”

“Because I couldn’t. I couldn’t stop."

"No." Oannes leaned forward, and Riam smelled the sea on him, kelp and brine and a sweetness that made his chest ache. "Because you knew. You've always known. You just didn't want to believe it, because believing it meant he chose. Teyo chose the sea. He chose me. He chose to leave you behind."

Riam's hand moved across the table, then over the scattered seeds, until his fingers brushed Oannes's wrist. The skin was cool and slick, not quite human, but beneath it he felt something that must've been a pulse. Faint. Irregular.

Oannes went still.

"You are real," Riam said. “Aren’t you?”

"As real as what you see. And what you feel.”

The fire died to embers. The tea went cold. They sat like that until the storm began to quiet.

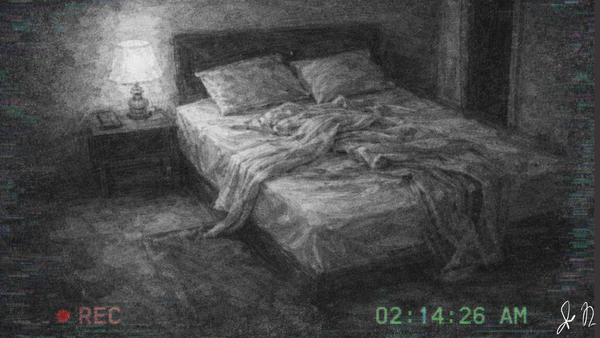

The rain broke near midnight. Riam stood at the door and watched the clouds tear apart, revealing a moon so bright it hurt his eyes. The rocks below shone wet and silver. The sea had calmed to a whisper.

"Come outside," Oannes said. “Please.”

He had not moved from the kitchen chair in hours. Now he rose, and the motion was fluid and not quite right, similar to how water shifted to find its level.

"It's freezing," Riam said.

"You won't feel it. Not if you're with me."

Riam followed him out without another word. They picked their way down the path to the rocks, Oannes barefoot and sure, Riam stumbling in his boots. The moonlight made everything strange. Made the familiar shapes of stone and sea transform into something older, something from before they had names.

Oannes stopped at the flat rock where Riam had left the pomegranate. The fruit was still there, untouched.

"You asked me to take something," he said. "In your letter."

"I didn't mean—"

"Didn't you?" Oannes turned to face him. In the moonlight his eyes were no longer brown. They were the deep grey-green of water seen from below, light filtering down from a surface far above. "Forty years, Riam. Forty letters. I've read them all…every one that reached the water, every one that didn't rot away before the tide could take it. You've asked me for death. For the mercy of forgetting. For one more hour with him. You've asked me for everything except the one thing I can give."

"What is that?"

"The same choice I gave Teyo."

The waves were lapping at Riam's boots now. He had not noticed the tide coming in, but the water was ankle-deep and rising. It was warm. It should not have been warm, as it was January, and the sea should have been cold enough to stop a heart. But it wrapped around his feet anyway.

"He didn't drown," Riam said. "You're telling me he didn't drown."

"He did. And he didn't." Oannes stepped closer, and the space between them was narrow now, intimate. "The sea takes, Riam. That's what the old stories say, and the old stories are true. But they don't say what the sea gives back in return. They don't talk about the ones who go willingly. The ones who choose it.”

"He would have told me. If he wanted…if he was going to—"

"Would he?" Oannes's hand came up, touched Riam's cheek, and the touch was cold and kind. "You wanted him to stay. He knew what you would say."

The water was at Riam's knees now. His trousers were soaked, clinging, and still he was not cold. The warmth was spreading through him, up his spine, into his chest. It felt like whiskey, or his love for it.

"He loved you," Oannes said. "He still does, in his way. But memory fades in the deep places. Names become sounds become nothing. He is not Teyo anymore, and I am not what I was before I went into the water. That is the cost."

"And you're offering me this cost."

"I can only offer the choice. Remain here, in your lighthouse, with your thoughts and your letters and your pomegranates. Grow old. Die with dignity. Become nothing but a story the village tells. Or—" He leaned in, and his breath was cool against Riam's mouth, tasting of salt and fruit. "Come with me. Become something new. Something that does not age. Does not wither. Does not mourn."

"Like Teyo.”

"Eventually. Yes."

The water was at Riam's waist. He could feel the current tugging at him, gentle but insistent. The rocks where he had stood for forty years were disappearing beneath the tide.

He could not imagine leaving the lighthouse. He pictured its quiet rooms, the narrow bed, the books he had read so many times the pages were soft as cloth, and he was far from done with them. But there was also the village, the handful of people who nodded to him when he came for supplies, even though for most, he had become invisible with age.

He wondered what Teyo might’ve said. Not this myth of Teyo, not the story he told himself at night, but the real one that was messy, selfish, inconvenient, loved.

Through it all, he had written letters. Every year, the same question dressed in different words: Why did you leave me? Why did you leave me? Why did you leave me?

He took Oannes's hand. "Show me," he said.

The tide rose around them, and they walked together into the sea.

The water closed over Riam's head, and he did not drown. Or perhaps he did. Perhaps drowning was not what he had been taught, with the lungs filling, the body fighting, the terrible surrender. Perhaps drowning was warmth spreading through him like wine, the pressure in his ears becoming music, the darkness opening into a thousand blues.

Oannes's hand in his was an anchor, he reasoned. An anchor to the self he was losing, to the world he was leaving behind.

This is what Teyo felt. This is what he chose.

They drifted. The moonlight filtered down, pale and fractured, illuminating things that Riam had no words for. Shapes that moved, that glowed, that watched with eyes like lamps. Oannes was beside him, and wherever Oannes was, the pressure eased, the cold retreated.

You're dying, a voice said, and Riam realized it was his own. You're dying and this is a hallucination, a fever dream, the brain's final gift.

But then Oannes turned to him, and his face in the underwater light was beautiful in a way that human faces were not. Serene, alien, luminous.

"Not dying," Oannes said, and his voice carried through the water as clearly as through air. "Changing. Always changing.”

He kissed Riam.

The taste of it flooded through him, sweet and bitter at once, the taste of fruit eaten in a garden he could never return to. His mouth filled with it, his lungs, his blood. He felt his feet lose their grip on the sandy bottom. Felt his body become lighter, stranger, less his own.

Let go, Oannes's voice said, inside his head now, part of him. What you were is ending. What you will be has no name yet.

Riam thought of his name. Riam. What did it mean? Who had given it to him? His mother's voice, saying it in anger, in love, in exasperation. Teyo's voice, laughing, teasing. His own voice, a litany of identity spoken into mirrors and silence and the long years of not knowing why Teyo had gone. I am Riam. I am Riam. I am—

He let go. The name dissolved. The memories went soft at the edges. He felt the sea remake him, cell by cell, thought by thought. It did not hurt. There was only heat and pressure and and the sensation of being held by something so vast that his entire life was a single droplet in its depths.

The last of the air left his lungs. The last of the light faded from his eyes. And in the darkness, in the silence, in the weight of all that water, Riam smiled.

The darkness held him down. He did not need to rise.

The storm passed in the night. By morning the sky was clear, the sea glass calm, the rocks below the lighthouse rimed with frost that glittered in the early sun.

Shrana Ohlsson found a pomegranate on the ground. She had come to check on the old man. Her grandmother had known him, years ago, and made Shrana promise to look in on him after bad weather. She arrived to find the lighthouse door was open, the fire dead in the grate, the kettle cold. His bed had not been slept in. His coat hung on its peg.

She walked down to the rocks, her boots slipping on the wet stone, and found the fruit sitting on the flat rock where it always sat, every winter, for as long as anyone could remember. But this year the pomegranate had not been taken by the tide. It sat there split and darkening, its seeds scattered across the stone like something meant for someone else.

She looked out at the sea. It was very still. Very blue.

"He walked into the water," she told the village later, at the pub, over a pint she barely touched. "I know how it sounds…well, I know it sounds mad. But I found his footprints in the sand. Just the one set, going down to the tide line. And nothing coming back."

They searched for five days. They never found a body.

Author's Notes

I wrote this story as a way to say thanks to one of our members who signed up for the paid tier after reading No Regrets. I asked them if they had any ideas or themes they'd like to see from me next, and they mentioned my other story—I Am the Wolf, I Am the Boy—from last September. So in many ways, The Pomegranate Man is in direct conversation with both of those stories.

As part of my general writing development, I spent a good portion of last year studying up again on Ursula Le Guin, specifically how she's able to write masterful, literary fantasy. Her work is so lyrical, mythologically grounded, and emotionally precise and formally beautiful. I can't hope to measure up, but my goal (at least) is to use folklore and liminal space (in this case between sea and shore) to examine tough emotions. That was the starting point.

The emotions I chose are a three-point cross between grief, choice, and transformation. The central question being "what does it mean to stop mourning?" For Oannes, I wanted to craft a truly original figure while drawing on some reimagined Mesopotamian mythology. Oannes is a fish-man sage, a bringer of knowledge. Here, I've twisted him into a psychopomp/transformer. My hope was that the story could use this lore without overly explaining it. I always want to trust readers to feel mythic weight even if they don't necessarily know the source. And hey, that's what these author's notes are for, right?

On that note, we've been getting more and more submissions for the magazine lately, and I know a lot of folks are trying to get a sense of what we accept for publication at Cetera. I should note that even as chief editor, my stories don't always make the cut! Natalia Emmons (our managing editor) has routinely slashed my work to the bone and constantly pushes me to make sure every detail and idea serves multiple purposes. I agree with her and want to see more of that from writers who submit fantasy to us. Note how in this story, the lighthouse represents isolation, vigil, and a beacon for what won't return. The pomegranate is an offering, a myth, a threshold between sweetness and rot.

Additionally, we read a lot of stories that have at least one theme as its beating heart. But please push your theme deeper. This story could've just been about mourning and grief and that's it. But I've read that story before. I wanted to say something a little different with this one. I had to really sit down and examine an uncomfortable truth, after all.

Even the good kind of transformation involves some kind of loss.

In other words, rebirth requires obliteration. Riam's choice, in the end, isn't easy or predictable. He could stay. He has his lighthouse, his books, his quiet life. The story doesn't make staying seem impossible or pathetic, which makes his choice to go feel weighty and real. At least to me.

Jon Negroni is a Puerto Rican author based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He’s published two books, as well as short stories for IHRAM Press, The Fairy Tale Magazine, and more.

Support Cetera

Paid members get exclusive perks like bonus stories, the ability to comment, and more. Plus you'd be helping us keep the bills paid. You can check out the subscription tiers below, or you can leave a one-time tip if that works better for you.