You're the Best

It seemed to matter that this was Christmas.

She met them at her sister’s house on Christmas afternoon. The driveway was already full, cars angled tight, bumpers close enough to kiss. She parked on the street and walked up with a bag that cut into her fingers. The porch light was on though it was still day. Inside, the heat was too high. Coats were piled on a chair. Someone had put on a record from before everyone got married. Her mother hugged her once and said, You made it, like it had been in doubt. Her brother was already drinking from a mug that was not meant for coffee. The tree leaned slightly to the left. An ornament she remembered breaking was whole again. She took off her shoes and lined them with the others. Nobody asked how the train was. They asked if she was hungry. She said not yet and stood by the counter until there was nowhere else to stand.

The house felt smaller than she remembered, or maybe it had always been this way. The ceilings might have been lower, though no one else seemed to notice. Everyone said it was good to be together again, and she believed they meant it, even if the room kept filling and emptying in a way that made her lose track of who had arrived. She thought she had been here last year, but that memory came apart when she tried to hold it. Her mother moved through the kitchen like this was her house and not a place she visited. People talked about traditions as if they had agreed on them. The same jokes came up, or versions of them, and were laughed at again. It seemed to matter that this was Christmas, though nothing about the afternoon felt different from other times they had gathered. She wondered if that was always true.

She did not sit right away, even when there were chairs. She stayed busy instead, which was easier to explain. She offered to help and then helped, which meant setting out plates, refilling the napkins, lining up forks that were already straight. She did not do this because she thought it mattered. She did it because this was what she did in rooms like this. There was a way to move that kept people from asking questions. She carried things back and forth—gravy boat, serving spoon, the bowl with the chips no one ate—until the table looked ready by some agreed-upon standard. Her mother had taught her this, not with words but with repetition, with the rule that idle hands invited comment. She knew this about herself and accepted it as fact. For a while, this was all there was. Just keep moving.

At the table, her uncle asked her if she was seeing anyone.

“No.”

“You sure?”

“Yes.”

“That’s new.”

“It’s not.”

There was a pause.

“You look tired.”

“I’m fine.”

“Work?”

“Mostly.”

Another pause.

“Well. We’re glad you’re here.”

She nodded and reached for the bread.

Plates passing, voices crossing, her name said once and then again, the question reshaped to sound kinder, to sound like concern. Someone mentioning the weather, someone else mentioning traffic, the same stories resurfacing with small edits, as if improved over time. She laughed when expected and not otherwise. She did not correct anything. She did not add detail. The meal moved forward without ceremony, without anyone saying grace, a habit now rather than a choice. Her sister watched her for a moment, then looked away, which felt like permission. Across the room, the tree lights blinked and stopped, blinked again, one bulb dark the whole time.

She had known this would happen, or thought she had, and still it surprised her when it did; the way her mother reached for her hand and then stopped, as if remembering too late what was allowed now. The gesture lingered anyway, unfinished, which felt worse than if it had never started. She understood then that the questions were meant as care, not judgment, and that the pauses were meant to give her room rather than take it away. It was not how she would have done it. It was how they knew how. The room settled back into its noise. No one mentioned the hand.

She remembered another Christmas, the same table set with fewer chairs. Her father had leaned back and said—You should stay longer this time!—and everyone had laughed. She had smiled and nodded, already counting the days. But she had not stayed then, either, and she would not stay now, because there was work waiting and a train schedule that did not bend, because it was easier to leave with a plan than to test how long welcome might last.

As though the day were winding down on its own, the light thinned and the kitchen cooled, and someone opened a window an inch to let the food smell out. She stood by the sink and watched her breath fog the glass, something she used to do as a kid when she didn’t want to talk. There had been other years when her aunt said, You know how she is, always passing through, like it was a joke that explained everything. Because of that, she had believed she was leaving by choice, that motion was a kind of freedom. She had not thought of it as running.

Her sister talked about the kids and the school district and the price of houses now, leaning against the counter and saying—You can’t keep doing this—like it was an observation more than an accusation. The words sat there while the water ran, while the dishes stacked up again, while she listened for something else underneath them. It took her a moment to understand what was meant: the missed birthdays, the empty chairs, the people who learned not to ask until the last minute, and so on.

She left at seven. The last train was at eight twelve. Other years, she had stayed later. She was learning how to go.

At the door, her mother said she would call tomorrow.

Standing on the porch, she realized no one followed her out, but she could feel her sister watching from the window. —It’s not a big thing, it’s just a little thing, her sister had said earlier, she remembered, just a little thing that adds up. Avoidance.

She could have stayed if she had wanted to, if she had said something different or nothing at all. She might have been there for breakfast, for the quiet after, if she had made that choice.

The porch was quiet. Her bag at her feet, her coat half-zipped, that familiar pause that always came before leaving. She did not turn back.

Her mother came out then and asked, Will you be home before it gets too late?

Standing there, shifting her weight, waiting. She had never slammed the door; never raised her voice; never said the thing that would have made the leaving tidy. No more tears, no more shouting, no more scenes to rewatch later: just the quiet accumulation of departures, less dramatic than anyone expected, easier to dismiss, which had once been called maturity. She had told herself this as the years passed, until it felt close to right.

It was calm. It would not be mentioned again.

“Jesus Christ.”

“You always do this.”

“Just say it.”

She turned back to explain, to soften what had already hardened, so that the leaving would not feel like rejection, like proof, like something she would carry alone while it kept happening without her. She said she would text when she got home. She said the train was late sometimes. She said, Don’t worry.

Her mother nodded—already tired, already rearranging the evening in her head, a woman who had learned not to ask twice; she had never chased after anyone.

She could smell the cold off the street, the metal of the railing, the faint sweetness from the tree inside, blinking unevenly, maybe.

“Be safe.”

“I always am.”

“You’re the best.”

She had often thought this was what leaving felt like, when the words were small and the meaning already decided: Be careful.

Afterward, it did not hurt the way she had imagined, not right away, not the way it had when she was younger, when she counted miles and exits. Instead there was the walk to the station: the cracked sidewalk under the streetlight; the bag cutting again into her fingers; the phone buzzing once and stopping; the house behind her with its lights still on, which she had once believed meant something; the cold settling in, steady and impersonal; the thought that tomorrow would look like yesterday, and the day after that, and that this was how patterns kept themselves.

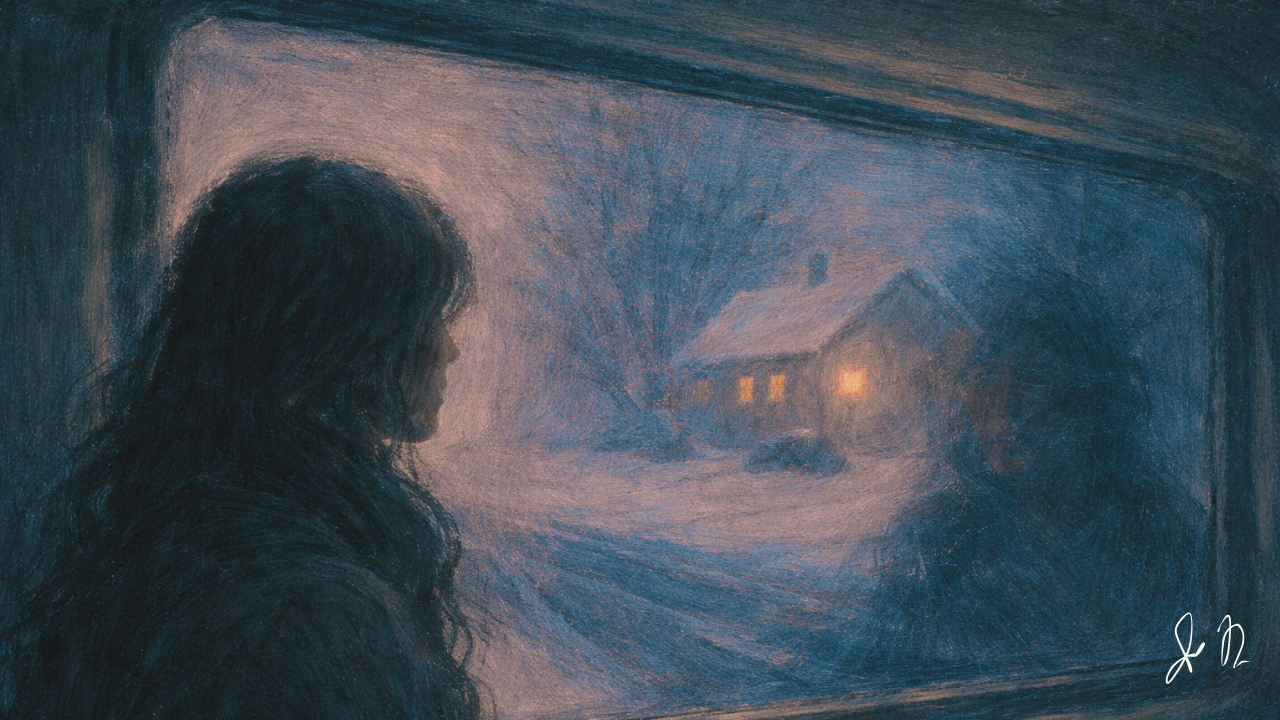

By the time the train arrived, she had stopped thinking about the house and started thinking about the ride, the seat by the window, the small relief of motion. It was the easiest part, the leaving itself, practiced and efficient, requiring no explanation. She found a place to stand and then a place to sit—watching the platform slide away and listening to the doors close. She told herself, as she had before; this isn’t forever, a phrase she heard once in church. For a while, it seemed true, until she forgot she had ever believed otherwise.

At the next stop, she realized she had left something behind, something she would need before morning.

She pressed a face on her phone.

“Well, did you check the bag?”

“Yes.”

“Then it’s not there.”

“I know.”

“You always forget one thing.”

“I know.”

“You have before.”

“Yeah.”

She got off the phone and then the train and stood on the platform while the doors closed again. She said her usual thing, that it would be fine.

Getting back on, she paused. The moment before.

The platform was too lit for the night: the yellow line scuffed and faded, the bench bolted to the concrete, the trash can with its lid half off—someone had kicked it again—steam lifting from the grates, her reflection doubled in the glass, then breaking as the train pulled in.

Later, she would see that she had been waiting, deliberately, without hurry, for the feeling to catch up to the act.

She took her seat, one by the window that felt borrowed. Here, years ago, she would have leaned her head back to steady herself, counting stations, loosening her grip on the bag, letting the rhythm do the work for her.

Would this be the last time?

On the glass, she couldn’t stop herself from watching one of the houses recede, its shape breaking apart as the train moved, the windows dimming one by one, a porch light left on, stubbornly. She saw it plainly—roofline, siding, the dark gap of the driveway, the street beyond.

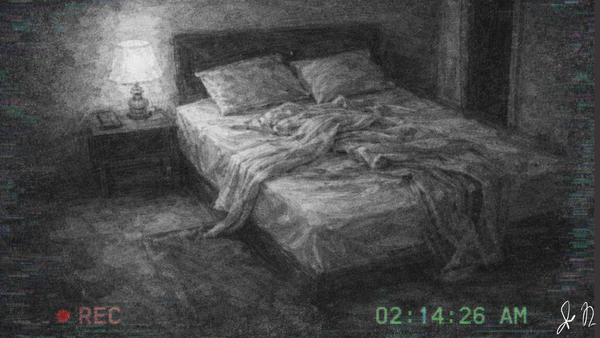

Later that night, she got home to put the day away. She had locked the door behind her and she had set the bag down by the chair, still wearing her coat. She turned on the lamp, checked her phone, washed her hands, stood there a moment longer than necessary. In the quiet of the apartment, in the small space between the door and the window, she found the thing she had not remembered to look for before, resting where it always did, still waiting.

Author's Notes:

Truth time. This is sort of a companion piece to "Holiday Party," which we published last week. You'll notice the similarities in the writing style and the obvious parallels in this being a holiday-themed story that is wildly depressing. Sorry about that.

But where "You're the Best" differs is in its central idea of avoidance being mistaken for maturity. And it's about how people like to stay in motion as a means of protecting themselves emotionally. Let's break down what's happening here.

One of the most frequent criticisms I've received of my own work is how distant the narrator tends to be. Ah, but I usually get this criticism for my fantasy writing. In my literary work, the distance is typically received as precise and narratively appropriate. Go figure. In this story, the third person is hovering just outside the protagonist, so close enough to register sensory details like a bag cutting into fingers...but it's remote enough to create this suffocating sense of dissociation.

For this particular story, I really wanted to play with temporal fragmentation, which is when you move fluidly between present action, memory, and something close to iterative time ("other years," "always," "had always been"). This is something I deeply love about Sally Rooney's novels, particularly her most recent one, Intermezzo. It creates the sensation of all Christmases collapsing into one Christmas, which is exactly the trap our protagonist experiences. This repetition that's calcified into pattern.

We never learn what was left behind, but that's because the story is about withholding. And I get that for some readers, this might be too frustrating. They might not want to be held at such a distance, and the emotional stakes can certainly suffer. But I kind of love letting the story be "wrong" in this way. I like making it a little imperfect, a little frustrating on purpose. That's what the best literary fiction should do, I think. It should make us sit with things we don't always want to sit with.

Happy holidays from all of us at Cetera Magazine. We're excited to publish some new stories pretty soon from a batch of new contributors, so thanks to all our subscribers for supporting our first year. Here's to the next one.

Jon Negroni is a Puerto Rican author based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He’s published two books, as well as short stories for IHRAM Press, The Fairy Tale Magazine, and more.

Support Cetera

Paid members get exclusive perks like bonus stories, the ability to comment, and more. Plus you'd be helping us keep the bills paid. You can check out the subscription tiers below, or you can leave a one-time tip if that works better for you.