Someone Lived There Too

The house on Seagrass Close is haunted. But the ghosts aren't angry. They're lonely.

I was warned about the house with kindness. The kindness that people on the Cape have perfected, which so perfectly sounds like hospitality when you first hear it.

At the coffee place on Commercial, the guy with the Red Sox cap poured my medium regular and said, “Off-season? You an artist or a lunatic?”

“Both,” I said, which was truer than I hoped it to be.

“Where you staying?”

I told him the lane and the number and watched his eyebrows climb. “That place is so old,” he said, testing the words on his lips. “Someone probably died there.”

“Yeah,” I said. “And?”

He laughed. “Suit yourself.”

I carried the coffee out to the car and sat a minute with the heat running, watching the bay throw dull light at a duller sky. The houses along the shore tried to look cheerful, but the clapboard peeled in places and the shutters hung like tired eyelids. In summer those same houses will grin wide and eat people whole. In November they’re just mouths waiting for winter.

My place was on a back road that remembered sand before asphalt. The sign said SEAGRASS CLOSE because on the Cape even a short dead-end has to sound like a children’s book. The house itself was one story with a little pitch in the roof and a dormer like a hat bandit...white once, gray now, the same gray that happens when salt wins the long game. A past-its-prime Cape with a square of lawn and a crooked flagpole and a hedge the color of old money. Out back, a scrape of marsh wanted to be part of the bay so badly, yet it failed every storm.

I unlocked the door and the door unlocked me. It did that, sometimes—old houses let you in or they don’t. This one sighed as if I were its kid and let itself be opened.

Inside wasn’t much. Cobwebs, old rug, the after-sweet scent of dry wood. Also a thin whiff of lavender that didn’t make sense. Definitely the same lavender you smell from sachets that old ladies tuck into drawers, except there were no drawers open and no sachets and no old ladies in this house. Not anymore.

I walked around with my coffee and my duffel, cataloguing like a cop the sofa with a sheet thrown over it (yellow once), a narrow mantle with a glass bowl of sand dollars, a dining table that had a wobbly leg someone had tried to hide with a coaster under the short foot, and the cupboard next to the back door with a little fish carved on it where a handle should be. When I opened that cupboard the smell of dead bugs hit me hard and good. There were rain slickers hung on hooks, two adult size, one kid. I left them alone.

I’m a painter when I can stand myself. Illustrations and hand-lettered covers when I can’t. People think being able to do both is a blessing, but most blessings come with a cord that goes around your wrists. Mine had been tightened in the roughest way these last few months until I mostly made outlines I didn’t fill in. I had come because my friend Hal said, Go to the Cape in November, Rena. Half the tourist traps are closed, you won’t have any excuses, and you’ll have fog, which is nature’s Vaseline filter. Hal was not wrong about fog, excuses, or me.

The bedroom opened my nose like an ocean in a Victorian novel, and yes the imagination did the heavy lifting for rot. But the bed was a good one, firm but merciful, and the dresser had a mirror that made me feel kinder about my face. I ran my hand along the top and spread the dust like sand on a blanket. The lavender was even stronger in here. There was a ceramic vase with a spray of it on the window ledge, the purple sunk to brown, the stems brittle. Weird, the plant should have been dead twice over, but it smelled like it had been cut yesterday.

Someone probably died there, the coffee man had said. He said it with such direct fatalism, a commonality for coastal folk who expect loss the way other towns expect incorrect weather forecasts. And he was probably right. People do in fact die in houses. But the bigger truth is that they live in them. They fill the walls until the walls are heavy with noise and then, someday, they go, and the noise curdles into a deep pressure that makes new people hear things.

The first odd thing was daylight changing in a room with no electricity turned on yet. I was in the kitchen eating pretzels out of the bag because I had not yet done the adult thing and gone to Shaw’s. The afternoon was dull and sulking, the sky bruising too much for the hour. The room bent that demented light into a flattened coin on the table. I picked the coin up and it warmed itself in my hand, as if someone had polished it with their palm mere seconds ago. I looked for the source and didn’t find one, as the one small window had a view of hedge and gray sky. I stood still, and the mystery light lingered in the silence with me, and then it was only the regular daylight again, begging me to take a nap and forget I exist.

The second odd thing was the door.

There were three interior doors: bedroom, bathroom, and a skinny closet that made a walk-in pantry if you were willing to walk in sideways. Each door had been painted a pale seafoam at some point, then painted white later, and both paints had fought with each other ever since. The bedroom door didn’t like to shut unless you invited it in a particular way, with your shoulder and a little patience. I learned its preferences the first night when the wind came in off the marsh and made the whole place practice its do-re-mi-fa-so. The second night, sometime after two, the bedroom door creaked open in a way that wasn’t wind and most certainly wasn’t me.

I woke to the small noise and lay there with my eyes shut because if this was a horror movie, then I wanted the cheaper matinee ticket where I die in my sleep. The lavender smell perked my nose. The floorboard just inside the door made an exasperated noise like someone trying not to wake a child. I opened my eyes and looked into the dark and the dark looked back the way it always does, equal opportunity. The door was open five inches. Nothing else.

“Okay,” I said to the room, low. “You do you.”

Look. I’m not brave. I am stubborn in the way that amounts to a cheap imitation of bravery. So I got up, shut the door, and went back to sleep. Because for me, exhaustion is better than exorcism, most nights.

The third odd thing wasn’t odd at all, not really. It was the height marks on the doorframe.

I found them on the third morning. I was walking the perimeter with my sketch pad, marking the scuffs and the places where paint bubbled and someone with patience had scraped it smooth and then given up politely. The marks were on the doorframe between the hall and the kitchen, showing pencil lines with dates. Nothing spooky about that. Every house that holds on long enough gets a doorframe like a prison tally, a record of successful growth.

The dates went from 1979 to 1986, then they just stopped. But also two names in a mother’s careful hand: THEO and LARK. Sometimes just a T., sometimes L. Oh, and I spotted a couple hearts on the early ones that embarrassed me to see. The last mark was higher than my shoulder and had a star next to it.

I put my fingers on the star and felt stupid about the way my chest collected water. People mark wins where they can, I guess. I mean a kid stood there tall for the first time in their little life and someone smiled at them for it. Then the wood kept a tidy record. That’s a kind of haunting too, I think.

I grocery-shopped that afternoon with an “ignorance is bliss” mentality, as if buying pasta was going to fix a lack of art in me. At the fish counter, a woman in a red fleece with “Marcia” on it made lemonade out of our nothing conversation.

“You the one renting on Seagrass Close?” she asked.

“Yeah.”

“That old cottage?”

“It’s a house,” I said, because that felt like a defense of something I hadn’t earned.

“Right,” she said, and made a face like she’d bitten a seed. “Just…folks say it’s got a draft that thinks for itself. But, well, folks do say a lot. You paint?”

It was a challenge not looking down at the faded paint stains on my overalls she'd obviously just spotted. “Yeah. Trying.”

“You know, sometimes the air in that cottage is wet with other people,” she said, and I was suddenly, irrationally sure her name wasn’t Marcia at all and she had borrowed the fleece from a sister or a lover or maybe a ghost and had never given it back. “Sometimes it’s just plain humidity.”

“Good...to know,” I said.

She wrapped the cod like it was a baby and handed it to me with that Cape look of half blessing, half good luck, you’ll need it.

The mail slot had nothing for me when I got home. The house had gone gray in the early dark, too. I turned on the light by the door and the bulb complained and then did its job. On the entry table was a little pile: the local free paper, two catalogues I hadn’t asked for, a promising new credit card opportunity, and a postcard with no stamp. The picture was of Provincetown in sepia, the pier shouldering itself into old water. On the back, a single sentence in a looping hand:

The lavender needs water even after it dies.

No signature.

I put the card on the fridge with a magnet shaped like a lobster and then took it back down and read it again just in case. Then I went into the bedroom and touched the brittle sprigs like I was testing a loose tooth. When I lifted the vase there was a faint round mark on the sill where it had sweated at some point, except the window hadn’t been open since I got there and the heat wasn’t on. I filled the vase in the sink because the options were believe a stranger’s advice or feel rude. The water seeped into the stems and the dried heads darkened from ash to something less dead.

That night I dreamed a room I’d never seen cheered when a man came through it. The cheer had the creak of real life in it—the chair leg’s groaning, the relieving sigh of a woman who knows where the good pan is, the knock of a boy’s heel on a baseboard because he is tall now and doesn’t know where his limbs end. The man had sea on him, a gravity of it, and the woman crossed her arms to hide her satisfaction. There was stew in a pot and it changed its mind about boiling when he kissed her at the back of the neck. A girl (Lark, I knew as if someone had told me at a party and I’d forgotten and pretended I knew all along) put shells in a row on the table like money.

When I woke, the bedroom light was different. It had that warm polish again. The door stood open five inches. Again.

I got up and, instead of shutting it, I stepped into the hall. The house held still like a wild thing that has decided it isn’t trapped. I could hear the marsh talking to itself outside, a series of wet whispers to no one but the moon behind the gray. The kitchen at the end of the hall was bright in the darkest fashion, like it had been saving up emergency light during the day when no one was looking.

On the table where my notebook sat, there was a sprig of lavender next to a pencil I didn’t leave there, its wood sharpened clean and perfect, far more than the janky handheld I carried. Apparently, someone had shaved it to a blade, and the shavings were the shape of little boats, curled and fragile. It would be a lovely prank if I knew anyone who had a key.

“Hi,” I said to the empty house, wondering if I had a right to give it a name in addition to a hello.

Nothing answered. Except the pencil wrote in a soft, willing way when I put it to paper, the line smooth as a tide line. I drew the door. Not from memory, of course. I looked up and drew what I saw, which was this: a door that had opened to five inches of invitation every night since I’d arrived; the paint that didn’t want to be white; the nick low down where a child had learned to ride a trike too fast down the hall. When I finished and put the pencil down, I knew I had drawn myself into it. My reflection in the window over the sink was ghosted in the door’s white, and if I shaded the white, I would shade myself out.

The next day I walked to the library to see the ghosts of the old town on display. The librarian was one of those women who has decided the world might be small enough to manage. She wore her silver hair like a crown she didn’t brag about, and when I asked about the house on Seagrass Close, she pursed her mouth and then turned her face into a filing cabinet.

“Which one?” she said, polite fencing.

“The one with the hedge and the flagpole. Was there a family—Theo? Lark?”

Her eyebrows had a private conversation. “Hm, yes, the Nicholases,” she said at last. “Benjamin, Alma, and the children. We have a town report from maybe...’82 mentions them. And a church bulletin…somewhere…with a supper for the fishermen’s families after a storm took four boats out of five but brought all the men back, praise be.”

“And later?” I asked.

“Yes, well, later we get bad with names,” she said. “People go. Gosh, that house has sat empty more than it’s sat full.”

Back at the cottage I tried to paint and got exactly nowhere and then exactly nowhere a little harder. Sometimes I can feel the hole where talent should be like a cavity my tongue keeps checking. Still, I did the responsible thing and cleaned a counter and felt 0% better. Late afternoon, with a light I could slice bread on, I took the little bowl of sand dollars off the mantle and ran my thumb along their dry faces. One was broken. Inside was the faintest star.

I didn’t hear the front door open, because in all honesty it didn’t. One minute the portrait over the table—the man with the stubborn mouth and the mustache from magazines our grandparents kept for the ads—stood a little crooked. The next minute it didn’t. The nail made no sound. The man looked levelly into the room like a teacher who already knew I didn’t do the reading and was going to be kind about it anyway.

“Thank you,” I said, and then felt awkward, and then didn’t.

I should tell you what the house did when I finally pulled at it. I had been waiting like I would with a shy cat. I had this steady presence, nothing grabby, no eye contact. And on the fifth night, the wind came strong enough to make the shrubs talk to themselves, sounding annoyed. I lay in bed with the lamp on, reading a book about loneliness. The lavender had decided not to be dead. The heads were still brown but the scent had a light above it now, like church. I turned the light off and the dark came simply and without malice.

That was when the door opened to more than five inches.

It swung to a soft stop as if a sensibly shod foot were behind it. The hall beyond showed a light that couldn’t be from a lamp. It had a golden domesticity I associated with Thanksgiving at other people’s houses.

I got up and stood in the doorway and waited for my legs to do their shaking so I wouldn’t have to be surprised later. The house waited, too. That familiar smell of lavender came over me like someone else's breath.

“Okay,” I said into the warm. “You win.”

In the kitchen, the table had more things on it than the things I had put there. There was a basket—wicker frayed in two places—full of clothespins. A pencil box with shavings like I’d seen. A coaster with a duck on it that had been under the short table leg was now exactly where coasters are designed to be. On the counter by the sink, a glass with milk in it that was probably not milk but water shot through with light.

When I touched the glass it went cold as a lake in November. The light in it rippled. I set it down and it made the sound of milk glasses set down a thousand times, that faint hollow report. Once, I thought, there was a boy who drank milk here and knocked the glass over twice a week and got scolded by someone who loved him. That sound had saved itself and now I was allowed to hear it.

At the far end of the kitchen, the back door stood open and showed not the marsh but a vague suggestion of what could be a marsh. Then it became a summer. I saw a woman’s elbow leaning on a railing and a man’s hat hung on the back of a chair and two kids at war over a checkerboard and a pot on the stove interfering with every other smell the way stew does. The light came from everywhere light usually didn’t. It felt illegal to stare. It felt like someone had given me their private mail by accident.

The woman turned her head. She looked toward me with a weary gentleness people often claim in their forties. I could see nothing of her face that wasn’t her. And I didn’t even know her.

She lifted her hand, slowly, as if to say I know you’re here.

“Alma,” I whispered, letting the right name arrive. “I’m sorry.”

I don’t know why I said sorry. Maybe for using her house without explicit permission. Or maybe for letting my own house back home get bad in the ways hers once had and then acting like I didn’t see it. Maybe because apology is as worthless as a nickel, even if you can technically spend it anywhere.

The scene took in a long breath and then let it go. The door closed with a little click. The kitchen was my kitchen again.

That night I drew until my hand cramped. Normally I draw plans and outlines and I invent things that don’t really exist. Tonight I decided to draw something I remember about the world for once. I drew the basket, the coasters, the exact way the summer-lake light licked the edge of the table. I drew the doorframe and the pencil marks and left the last mark unshaded; I couldn’t bring myself to steal the star with graphite. When I put the pencil down it had become small with work and felt like a blessed little thing I hated dearly.

I slept the way I usually do after a long cry, which I had done, though I couldn’t have told you exactly when it started. Maybe when the portrait straightened. Or right after the milk glass made its small sound. And when the door said I know you’re there and meant it kindly.

In the morning the lavender stood up straighter in the vase. The heads had deepened in color like the house had been feeding them small sunrises in the night. I made coffee and poured it into the mug with the chip, as I have always preferred the damaged thing that keeps trying. On my way past the doorframe I saw a new pencil mark.

It was a bit tiny and had the same hand as the older ones, only not as strong. The date was the day before today. There was no initial. Just a tiny line exactly at the height of my shoulder.

Now, if you have ever had a house acknowledge you, you know that the floor will start to feel very different beneath your feet, like you’ve been given privileges or put on notice. I put my fingers on the new mark the way I had on the star and I laughed, a small surprised sound that made my throat sting.

“Okay,” I said to the house, which was also to the dead and the not-dead and to my old cowardice. “All right.”

Everything after that is easy stuff, which sounds simple when written down. I worked. The painting came. I stopped guessing at lines I didn’t intend to carry and I just carried them. I cooked two nights in a row and didn’t order pizza once. I bought a shell at the thrift store that looked exactly like a plastic knock-off until I put it to my ear and heard the oncoming train of the tide. I called my sister and didn’t just leave a message in the recesses of her life, I waited until she answered and then I told her the thing I had been saving in case love had a cap on it. (It doesn’t.)

I went back to the library and found, with the librarian’s help, an article from 1987 with a flattened picture of four people, the headline about a fundraiser for a young widow with two children after a fall on the docks took a fisherman’s footing and then his life; the names: Alma, Theo, Lark; a list of pies that had been baked; a note about how the house on Seagrass Close had been painted by volunteers the following spring.

The portrait over the table was straight as ever that night. I raised my glass of not-milk water over to the man with the mustache and said, “Thanks for coming home every time until you couldn’t.”

I do not pretend the house was mine. When the storm hit late that week and made the road flood in two places and brought wharf planks down the channel like rough funerals, I set candles on the mantle and let the house sing its wind songs. The lights went out at six and came back at nine and in between the kitchen didn’t scare me even once. I sat at the table and drew in the candle glow, which was a fat, medieval light that made the room feel like it knew a secret prayer that actually worked. Somewhere in that three hours a small weight settled at the chair beside me and then leaned away, careful not to startle. I didn’t look up. I didn’t need to. The house and I had decided on the amount of seeing that was kind enough.

By morning, the postcard on the fridge had new writing on it. The ink looked like it had been waiting in the card all along and had just decided to arrive.

It said: Thank you for keeping the door open.

I bought fresh lavender the next market day and didn’t tell myself I was doing it for the scent. I was doing it for the conversation. You keep up your end. You water even what everyone else thinks is dead.

On my last night I finished the painting. It was a painting of the door, of course, with the hall keeping very still and the kitchen full of a light that had learned to keep its secrets a little better. If you look close you can see a reflection in the glass of the framed picture on the wall, the one with the man who never entirely came home. The reflection is a woman standing in the doorway. She has a messy ponytail and the posture of someone who is trying to be a decent guest. It is not a perfect likeness, no painting is. But she is there.

I washed my brush in the sink and stood with my hands on either side of the basin in a posture I’ve seen in bad movies and holy books. The house made its settling noises and the marsh made its wild ones. I turned out the lamp by the door and the dark came kindly again. In the bedroom, the vase of lavender waited for me like a harbor light.

The door opened five inches.

“Goodnight,” I said.

They said someone died there. At the coffee place, at the fish counter, in my sister’s tender voice when I told her where I was. Maybe that’s true. You could taste it in the air, a shard. But when I turned out the light, I swear I heard someone breathing beside me. And it reminded me that someone lived there, too.

Authors' Notes:

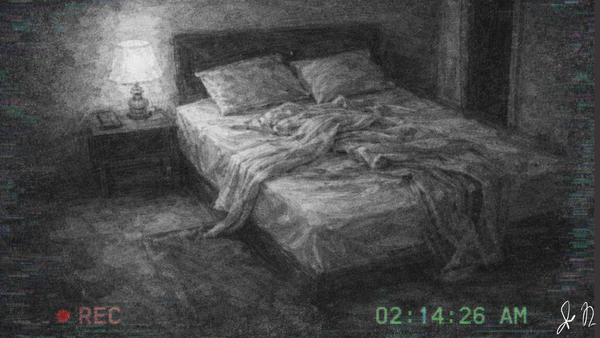

We're finishing off our October of Horror with a three-person effort on this week's story. That's right, Someone Lived There Too was created by three of us here at Cetera Magazine: Jon Negroni (person writing this part), Natalia Emmons, and Bridget Serdock.

Bridget came up with the original concept after pitching their idea about a misunderstood Cape house. Their original note was:

It's weird that we see ghosts as exclusively malevolent things in the US. I'm trying to parse through how our initial thought when we see an old house is "wow, someone died there. it's haunted" and not "wow, someone live there and loved it so much that they didn't leave" or "someone lived there and you can feel their ghost because the things we touch and love always have a piece of us in it."

From there, Bridget drew up the artwork you see at the beginning of this story, where it's a dual interpretation of a "haunted" house, literally "reframing" itself down to the picture frame.

Natalia, our managing editor, had an idea to build an original story around this concept to go with the comic. She pitched me a flash fiction piece, just under 1000 words, that is the skeleton of what you just read above. After reading it, I noticed a lot of similarities to Stephen King's approach to writing cyclical horror, and I took a pass at expanding the story into 4200 words with multiple scenes, and Natalia provided the final edits and a few rewrites.

This is our first big collaborative effort and I think it worked out quite well. Mainly because we found a way to go beyond the typical haunted house narrative and tell a story about cozy grief and artistic paralysis. Which is fitting, no?

You'll notice that the story, while concocted by three people, still employs a measured, contemplative pace that attempts to mirror both the off-season Cape Cod setting and the main character's emotional state.

For example, the opening establishes the story's central tension through the coffee shop warning—"Someone probably died there"—but then immediately subverts expectations by having Rena respond with indifference. This sets up the story's deeper concern with how life persists in spaces after their inhabitants are gone.

One of Natalia's biggest contributions was in deciding how to treat the supernatural elements. The "haunting" progresses through gentle intrusions (mysteriously warmed light, lavender that won't die, doors opening to precise measurements) rather than traditional scares. These manifestations feel less like violations than invitations, a house trying to communicate in the only language it has. (You should also check out Open Concept here at Cetera if you haven't already, which does a very similar haunted house tale in even more personified fashion).

The height marks on the doorframe serve as the story's emotional anchor. They're simultaneously the most mundane detail (every family home has them) and the most poignant (they stop in 1986, presumably when Benjamin died). So when a new mark appears at Rena's shoulder height, dated the day before, it's the house's way of marking her presence and accepting her into its chronology. That, by the way, was all Natalia.

Whereas Rena's narrative voice is distinctive and extremely Bridget. Self-deprecating but not self-pitying, observant but not detached. Lines like "I'm not brave. I am stubborn in the way that amounts to a cheap imitation of bravery" reveal someone who knows herself well enough to be honest about her limitations. Rena's artistic block mirrors her emotional state and her initial relationship with the house.

Most of my contributions stem in the prose and structuring. I wanted to infuse this story with unexpected metaphors that feel both fresh and exciting. So I wrote about houses that "grin wide and eat people whole" in summer, fog as "nature's Vaseline filter," exhaustion being "better than exorcism most nights." I wanted to make sure though that the writing manages to be both lyrical and grounded, never letting its "poetry" overwhelm the emotional truth of the story.

I also wanted to have the recurring motif of lavender—dead but fragrant, brittle but somehow alive—to work as a helpful metaphor for how love and memory persist in spaces. The instruction to "water even what everyone else thinks is dead" becomes the story's thesis about attention and care.

At its heart, this is a story about the human need to be seen and acknowledged. Rena arrives at the house unable to create, carrying some unnamed grief or failure (her damaged relationship with her sister, her artistic block). The house, holding its own grief, recognizes a kindred spirit. Their mutual acknowledgment becomes healing.

The story also explores how we inhabit spaces temporarily but meaningfully. Rena never claims ownership of the house; instead, she becomes part of its continuing story. The final image of her reflection painted into the door's white paint suggests that we leave traces of ourselves in the spaces we occupy, just as they leave traces in us.

I'm so glad Natalia pushed for the story to have this much restraint in its craft. We never over-explain the supernatural elements or force bombastic, emotional revelations. The ghostly manifestations could be read as purely psychological—a lonely artist projecting meaning onto an old house—but the story doesn't insist on this reading or its opposite. I really think it exists comfortably in ambiguity.

And yes, the ending resists the urge for dramatic closure. Rena doesn't solve the family's tragedy or lay their spirits to rest. Instead, she simply acknowledges them, and they acknowledge her. It's a mutual recognition that allows both parties to continue existing, slightly changed.

Bridget Serdock is an illustrator and editor for Cetera Magazine. They're also a producer of Fantasy Writing For Barbarians. "I am nothing if not kinda heartwarming in an aggressive way."

Natalia Emmons is the managing editor of Cetera Magazine and one of its cofounders. She mainly writes short fiction, poetry, and extremely long text messages about the perils of run on sentences.

Jon Negroni is a Puerto Rican author based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He’s published two books, as well as short stories for IHRAM Press, The Fairy Tale Magazine, and more.

Support Cetera

Paid members get exclusive perks like bonus stories, the ability to comment, and more. Plus you'd be helping us keep the bills paid. You can check out the subscription tiers below, or you can leave a one-time tip if that works better for you.