That's Your Problem to Solve

The most detached therapist in the world just met his perfect match. A woman addicted to being ignored.

Gabriel Hayes sat in a folding chair that cost eleven dollars at Home Depot and charged people five hundred an hour to hear him say five words. The chairs were uncomfortable on purpose. His office used to be Nails by Nancy until Nancy defaulted on her lease, and Gabriel could still smell acetone under the industrial-strength air freshener that promised “Ocean Breeze” but delivered something closer to “Chemical Spill at Sea World.”

“My husband left me for his CrossFit trainer,” said Mrs. Kellerman, a woman in her fifties who wore athleisure in a way that suggested she’d given up on actual leisure. “She’s twenty-six and can deadlift him.”

Gabriel adjusted his laminated desk nameplate. It read “Gabriel Hayes, Radical Non-Help Coach” in Comic Sans font because the print shop guy said it looked friendlier. Gabriel had specifically requested unfriendly, but, well, Comic Sans was also cheaper.

“That’s your problem to solve,” Gabriel said.

Mrs. Kellerman nodded eagerly and pulled out her checkbook. This was her fourth session. Gabriel had said the exact same five words every time, and she kept coming back like a lab rat hitting a button for cocaine.

“Same time next week?” she asked, already writing the check.

“If you want,” Gabriel said. He didn’t do appointments. Appointments implied caring about whether people showed up.

After Mrs. Kellerman left, Gabriel rearranged his motivational posters. “YOU’RE ON YOUR OWN” hung next to “STOP ASKING ME” and his personal favorite, “NOT MY CIRCUS, NOT MY MONKEYS,” which he’d bought on Etsy from a woman in Sacramento who specialized in sarcastic needlepoint.

Gabriel had discovered his gift for not helping people three years ago during his own recovery. Twenty years of marriage counseling, family interventions, and trying to solve everyone’s problems had cost him three wives, a hernia from stress, and the ability to watch movies without offering suggestions to characters who couldn’t hear him. His therapist had suggested Al-Anon. His sponsor had suggested boundaries. Gabriel had gone nuclear and decided to weaponize the very concept of indifference.

The business model itself was accidentally brilliant. San Francisco was full of people who’d been so coddled by therapists, life coaches, and app developers promising to optimize their feelings that they’d forgotten how to make a single decision without professional validation. Gabriel offered the opposite. He would give these people expensive, artisanal neglect.

His waiting room featured magazines from 2019 and a sign that read “PLEASE DO NOT SHARE YOUR FEELINGS WITH OTHER CLIENTS.” The bathroom had a mirror with a sticky note that said “THIS PERSON IS YOUR ONLY HOPE” with an arrow pointing down.

Gabriel was reorganizing his collection of self-help books turned backward so only the spines showed when a random woman walked in. She didn’t knock, nor did she wait to be invited. She just appeared in his doorway clutching a manila folder.

“I need to hire you,” she said.

“That’s your problem to solve,” Gabriel said automatically.

The woman sat down in the client chair without being asked. “Perfect. That’s exactly what I need. I’m Jennifer.” She reached out a hand. “Jennifer Kyuha.”

Gabriel almost shook Jennifer’s hand but instead ignored her until she relented. He studied her the way a chess player studies an opponent’s opening move. Most clients came to him desperate for permission to give up on someone else. Jennifer looked like she was conducting a job interview.

“What’s your problem?” Gabriel asked. He’d learned to start sessions this way because it cut through the small talk that made his skin crawl.

“I’m a pharmaceutical sales rep.”

“That’s your—”

“And I’m addicted to paying people to dismiss me,” she said, cutting him off and opening her folder. “I’ve spent thirty-one thousand, four hundred and twelve dollars in the past eighteen months on therapists, coaches, consultants, and one very expensive psychic who told me my problems were caused by past-life karma and that I should stop bothering her about it.”

Gabriel blinked. In three years of professional indifference, no one had ever presented their psychological dysfunction with PowerPoint-level organization.

“I have a spreadsheet,” Jennifer continued, producing a printed chart. “Dr. Harris charged me four hundred an hour to tell me I was too focused on external validation. Dr. Nguyen took three hundred and fifty to explain that I needed to develop internal resources. The life coach on Valencia, I forget her name, got two thousand upfront and then ghosted me after sending a text that said ‘You’re not ready for transformation.’”

“And you…liked this,” Gabriel said. It wasn’t a question.

“I loved it. Every dismissal from them felt like truth. Every rejection was pure, unfiltered honesty. The psychic was my favorite because she actually seemed annoyed that I existed.”

Gabriel leaned back in his Home Depot chair. Jennifer was either the most self-aware person he’d ever met or completely insane. In his experience, the two categories overlapped significantly.

“How’d you hear about me?” he asked.

“Well, your Yelp reviews are fascinating. Mrs. Walzack wrote, ‘Gabriel Hayes told me my marriage problems weren’t his concern and I’ve never felt more empowered.’ Mr. Shaw said you charge five hundred dollars to basically ignore people and it changed his life. Someone named Aidan left a one-star review that just said ‘He wouldn’t even pretend to care’ with four crying-face emojis. It almost made me weep.”

Gabriel had never read his own reviews. The idea of caring what people thought about his not caring seemed counterproductive. “So then you understand quite clearly that I don’t actually help people,” he said.

“I know. That’s why I’m here.”

“I mean, I literally do nothing. You pay me five hundred dollars and I tell you your problems aren’t my responsibility.”

“Yup.”

“And then you leave.”

“Perfect.”

Gabriel looked at Jennifer’s folder, her spreadsheet, her earnest expression, and her strangely calm demeanor. Something was wrong here. His entire business model depended on people who needed to be told they didn’t need help. Jennifer seemed to actually not need help, which made her unhelpable, which made her…his problem.

“That’s your problem to solve,” he said, testing.

Jennifer smiled. “Thank you. Same time next week?”

Three weeks later, Gabriel was experiencing the existential crisis of his life. In the old days, he would have talked it all through with a therapist. But his current self was supposed to handle the enigma of Jennifer Kyuha entirely on his own by ignoring it. Jennifer had become his most regular client and his biggest professional challenge. Every session followed the same pattern. She would present a problem with clinical precision, he would dismiss it with his usual phrase, and she would thank him like he’d just performed open-heart surgery.

“My sister wants me to be maid of honor at her destination wedding in Cabo,” Jennifer said, consulting what appeared to be actual notes. “The dress costs six hundred dollars, the bachelorette party is in Napa, and she’s planning activities that require me to pretend I like her fiancé, who once told me that pharmaceutical sales was basically legal drug dealing right before his best friend made a barely subtle pass at me.”

“That’s your problem to solve,” Gabriel said.

“Excellent. Also, my downstairs neighbor has been playing the same Spotify playlist at full volume since Tuesday. It’s just Adele’s ‘Someone Like You’ on repeat. I think she’s going through a breakup, but the walls are thin and I’m starting to have violent fantasies about Adele herself.”

“That’s your problem to solve.”

“And my mother called to say she’s disappointed that I’m thirty-two and still single, but also that she doesn’t like any of the men I’ve dated, which creates an interesting logical paradox about her expectations for my romantic life.”

Gabriel paused. This was the kind of maternal double-bind that usually required forty-five minutes of careful unpacking. His old self would have asked follow-up questions about family dynamics and attachment patterns. His current self had exactly one response.

“That’s your problem…to solve,” he said, but something in his voice had shifted.

Jennifer noticed immediately. “You almost sounded like you cared just then,” she said. With almost serial killer eyes.

“I didn’t.”

“You hesitated before you said it. Like you were actually thinking about my mother.”

Gabriel felt a familiar tightness in his chest, the same sensation he used to get right before diving into someone else’s psychological deep end. He breathed carefully and reminded himself that caring was the enemy of boundaries.

“Your mother isn’t my problem,” he said.

“No, but you thought about her for a second. I could see it.”

Jennifer leaned forward in her chair. For the first time since she’d started coming to him, she looked genuinely curious rather than professionally satisfied. “What did you used to do?” she asked. “Before all…this?”

“That’s your problem to solve.”

“You’re a recovering helper, aren’t you? Like, a serious one. Marriage counselor? Family therapist?”

Gabriel stood up. The session wasn’t supposed to go this direction. Jennifer was supposed to thank him and leave, not conduct an interview about his personal history. “Time’s up,” he said.

Jennifer checked her phone. “We still have twenty minutes.”

“Sessions end when I say they end.”

“That’s not how this works. I paid for an hour.”

“Sue me.”

Jennifer gathered her folder and stood up. At the door, she turned back. “You know what’s interesting? You’re the first person I’ve paid to dismiss me who actually seems conflicted about it.”

After she left, Gabriel sat in his uncomfortable chair and stared at his motivational posters. “YOU’RE ON YOUR OWN” looked back at him with what might have been judgment. He tried to remember why he’d started this business in the first place, but all he could think about was Jennifer’s mother and the impossible standards that created daughters who paid strangers to ignore them.

Gabriel’s Tuesday was booked solid with people who needed professional neglect. At ten AM, Joshua Roth wanted validation that his roommate’s dirty dishes weren’t his responsibility. At eleven, Sandra Lin needed permission to stop calling her adult son every day. At noon, Dr. Gina Hartley, an actual psychiatrist, paid five hundred dollars to hear that her patient’s transference issues weren’t Gabriel’s concern.

“It’s liberating,” Dr. Hartley had said. “I spend all day solving other people’s problems. Coming here is like a vacation from caring.”

Gabriel understood this, truly. His entire client base consisted of helpers who needed help not helping. The irony wasn’t lost on him that he’d created a helping profession dedicated to not helping, which made him a helper again, which was the exact thing he was trying not to be.

Jennifer arrived at her usual four PM slot carrying a different folder and wearing what Gabriel had learned to recognize as her “complicated problem” expression.

“I need to tell you something,” she said, sitting down. “I’ve been lying to you.”

Gabriel felt his stomach drop. In recovery circles, honesty was supposed to be healing, but in his experience, the truth usually made everything worse. “Uh…About what?”

“I’m not actually addicted to being dismissed. I mean, I was, but that’s not why I keep coming here.”

Jennifer opened her new folder and pulled out what appeared to be a psychological profile. Gabriel’s psychological profile.

“Where did you get that?”

“I know people. Pharmaceutical sales isn’t a far cry from mental health quacks.” Jennifer spread the papers on her lap like a hand of cards. “Gabriel Hayes, licensed marriage and family therapist, specializing in codependency and addiction counseling. Three marriages ended due to what your ex-wife Sharon described in her divorce filing as ‘compulsive caretaking and inability to maintain appropriate professional boundaries.’”

Gabriel stood up. “Session’s over.”

“You lost your license after a client filed a complaint that you were providing free therapy to her entire extended family, including her mother-in-law’s book club and her brother’s girlfriend’s roommate.”

“Get out.”

“You started this business because someone at Al-Anon told you that you needed to practice detachment, and you decided to turn radical detachment into a revenue stream.”

Gabriel moved toward the door, but Jennifer didn’t follow.

“Here’s the thing,” she said. “I don’t actually want to be dismissed. I want to be seen by someone who’s good at seeing people but has committed to not helping them. It’s like being understood by someone with zero agenda. Do you have any idea how freeing that is?”

Gabriel stopped moving. “No. What are you even talking about?”

“I’m talking about how you’re the first person I’ve met who’s as messed up about helping and being helped as I am, but from the opposite direction. You can’t stop wanting to fix people. I can’t stop wanting to be broken. We’re like complementary disorders.”

Jennifer stood up and walked to Gabriel’s motivational posters. “‘You’re on your own,’” she read aloud. “‘Stop asking me.’ ‘Not my circus, not my monkeys.’ Sheesh. You know what these really say? ‘Please don’t make me care about you because caring about people is the thing that destroyed my life.’”

Now Gabriel felt like someone was performing open-heart surgery on him. And without the anesthesia.

“That’s your problem to solve,” he said, but the words came out whispered.

“See? You can’t even say it with conviction anymore.” Jennifer walked back to her chair and sat down. “I have a proposal. What if we try actually helping each other?”

“I don’t help people.”

“And I don’t ask for help. But maybe we could make an exception. Just for today.”

Gabriel looked at Jennifer sitting in his client chair, holding his psychological profile, offering to break the one rule that kept his entire world functioning. Everything in his recovery told him to say no. Everything in his professional training told him to maintain boundaries. Everything in his business model told him to take her money and send her away.

“That’s your problem to solve,” he said, before leaving the room.

Gabriel spent the next week avoiding Jennifer’s proposal by booking extra clients and working late. He saw seventeen people in five days, collecting $8,500 for saying the same five words 68 times. His record was Thursday afternoon when he told Mrs. Bryant that her son’s gambling addiction wasn’t his problem, her husband’s erectile dysfunction wasn’t his concern, and her mother’s hoarding situation wasn’t his responsibility, all in the span of twelve minutes.

But Jennifer’s words had lodged in his brain like a song he couldn’t stop humming at the worst possible moments. “Complementary disorders.” “As messed up about helping and being helped as I am.” “What if we try actually helping each other?”

Gabriel had built his entire recovery around the idea that caring was toxic, but Jennifer made caring seem like a choice rather than a compulsion. She wanted to be seen without being fixed. She wanted to be understood without being solved. Gabriel had never considered that these things might be different.

On Friday, Jennifer didn’t show up at her usual time. Gabriel waited in his office for twenty minutes, which violated his own policy about not waiting for clients. At 4:25, he walked to the botanica next door where Mrs. Valdez sold candles for love, money, and spiritual cleansing.

“You looking for that Chinese girl?” Mrs. Valdez asked. “She came by yesterday asking if I knew anything about you.”

“What did you tell her?”

“I told her she’s too pretty for you. But also that you seem like a nice man who’s afraid of his own shadow. She bought a candle for clarity and one for protection. Said she might need both.”

Gabriel walked back to his office and sat in his client chair instead of his own. The view from this angle was different. He could see the water stains on the ceiling, the places where Nancy’s nail art posters had left marks on the walls, the way his desk created a barrier between where he sat and where people needed him to be.

At 5 PM, his phone rang.

“Gabriel Hayes Radical Non-Help Coaching.”

“Hi, it’s Jennifer. I’m in the emergency room at UCSF.”

Gabriel nearly fell off the chair. “Wait, what? What happened?”

“My sister’s wedding is tomorrow and I had what I think was a panic attack driving to the airport. I couldn’t breathe and my hands went numb and I pulled over and called 911.”

“Are you okay?”

“Yeah. The doctor says it’s anxiety. They want to give me Ativan and send me home, but I don’t have anyone to drive me and I can’t afford an Uber because I spent my last five hundred dollars on you.”

Gabriel looked at his motivational posters. “YOU’RE ON YOUR OWN” stared back at him with what now seemed like cruelty rather than wisdom.

“What do you need?” he asked.

“I need someone to pick me up and drive me home and maybe sit with me for a while until the medication wears off, but I know that’s not your job and I’m sorry for calling you and I know this isn’t your problem to solve.”

Gabriel was already reaching for his car keys. “Jennifer?”

“Yeah?”

“It’s my problem now.”

Gabriel found Jennifer in the emergency room waiting area, sitting under fluorescent lights that made everyone look like they were dying. She was still wearing the dress she’d apparently planned to travel in, wrinkled now and stained with what looked like coffee. Her folder was in her lap, but for the first time since he’d met her, she wasn’t consulting any papers.

“You came,” she said when she saw him.

“I was in the neighborhood.”

“The hospital is three miles from your office. That’s like twelve miles in SF traffic.”

Gabriel sat down in the plastic chair next to her. The emergency room smelled like disinfectant someone had used less than a hour ago to cover up something foul, a combination of chemicals that reminded him of visiting his grandfather during the last stages of his liver disease. His grandpa had been a drinker and a charmer who could talk his way out of any consequence except death. Gabriel had spent those final hospital visits trying to save a man who’d never asked to be saved.

“Right, so tell me more about your sister’s wedding,” Gabriel said.

Jennifer looked surprised. “You actually want to hear about it?”

“I want to understand why thinking about it sent you to the emergency room.”

Jennifer went quiet for a moment, then opened her folder. Instead of her usual organized notes, she pulled out a crumpled wedding invitation.

“She’s marrying her college boyfriend. They’ve been together for eight years. They have a house in Sacramento and a golden retriever named Kringle and a five-year plan that includes children and a vacation home in Tahoe.”

“Sounds nice.”

“Yeah, it is nice. That’s the problem. She asked me to be her maid of honor because she loves me and wants me to be part of her perfect day, and I said yes because I love her and want her to be happy.”

Gabriel waited. He’d learned that silence was often more useful than questions.

“But I hate weddings,” Jennifer continued. “I hate the forced celebration and the expensive dresses and the way everyone pretends that marriage is a guarantee instead of a really optimistic guess. And I hate that I can’t tell her this because it would hurt her feelings, and I hate that I’m going to spend a thousand dollars and three days pretending to be someone I’m not.”

“So don’t go.”

“I can’t not go. She’s my sister.”

“You had a panic attack driving to the airport. Your body is literally rejecting this plan.”

Jennifer looked at the wedding invitation. “But if I don’t go, I’m a terrible sister. If I do go, I’m a fraud. Either way, I’m failing at being a person.”

Gabriel recognized this kind of thinking. It was the same logic that had driven him to counseling other people’s families for free, the belief that love required self-erasure.

“What if there’s a third option?” he said.

“Like what?”

“What if you call your sister and tell her the truth? That you love her and want her to be happy, but weddings make you anxious and you don’t think you can handle being maid of honor?”

Jennifer stared at him. “You’re giving me advice.”

Gabriel realized she was right. Somewhere between the emergency room and the wedding invitation, he’d stopped being a professional boundary-setter and started being a person who cared about another person’s problems.

“Shit,” he said.

“You just helped me.”

“I know.”

“How does it feel?”

Gabriel considered this question rather carefully. For three years, he’d avoided helping anyone as a form of emotional sobriety. But sitting in the emergency room with Jennifer, offering actual solutions to her actual problems, he didn’t feel the familiar spiral of codependent panic. He felt useful in a way that was contained and voluntary.

“It feels like…like helping someone who doesn’t need to be saved,” he said.

Jennifer smiled. “Yeah. Maybe that’s the difference.”

A nurse called Jennifer’s name. The doctor wanted to see her before discharge, probably to lecture her about stress management and suggest she follow up with her primary care physician.

“Will you wait for me?” Jennifer asked.

Gabriel looked around the emergency room at the other people waiting for news about people they cared about. Six months ago, he would have stayed all night and driven Jennifer home and probably offered to call her sister for her. Three months ago, he would have told her that waiting wasn’t his job and left immediately.

Tonight, he just nodded.

Gabriel drove Jennifer home to her apartment in the Mission, a one-bedroom above a taqueria that smelled like the best carnitas he hadn’t tasted yet. Jennifer had called her sister from the car and explained that she was having anxiety about the wedding and thought it would be better if she wasn’t maid of honor but would love to come as a regular guest instead. Her sister had been understanding, which Jennifer admitted she hadn’t expected.

“I thought she’d be furious,” Jennifer said as Gabriel walked her to her door.

“People are usually more reasonable than we think they’re going to be.”

“Is that professional insight or personal experience?”

“Both.”

Jennifer unlocked her apartment door, then turned back to Gabriel. “What happens now?” she asked. “With us, I mean. With whatever this is.”

Gabriel had been thinking about this during the drive home. Jennifer was right that they had complementary disorders, but she was wrong about what that meant. Gabriel didn’t need to learn how to help people again. He needed to learn how to help people without losing himself in the process. Jennifer didn’t need to learn how to be ignored. She needed to learn how to be seen without disappearing. Maybe.

“I think,” Gabriel said, “we figure out what healthy helping looks like. Together.”

“Does that mean you’re firing me as a client?”

“It means I’m offering to be your friend instead.”

Jennifer smiled. “Friends don’t charge five hundred dollars an hour.”

“No, but they do show up at emergency rooms when you call them.”

“Hm. That’s true.”

Gabriel turned to leave, then stopped. “Oh, and Jennifer? Next week, instead of coming to my office, you want to just get coffee? Like normal people?”

“Sure. I’d like that. But I have one condition.”

“What’s that?”

“If I start telling you about my problems, you’re not allowed to say ‘That’s your problem to solve.’”

Gabriel laughed with his entire chest. “Deal. But if you start trying to pay me to ignore you, I reserve the right to tell you that’s ridiculous.”

“Deal.”

Gabriel walked back to his car feeling lighter than he had in years. His phone buzzed with a text from Mrs. Kellerman asking if she could book an emergency session to discuss her husband’s return from CrossFit training. Gabriel looked at the message, then typed back: “I think you should talk to an actual therapist about this. I can recommend someone.”

He sent the text and drove home through the Mission District, past the botanica where Mrs. Valdez was probably selling candles to people who needed to believe in magic, past the strip mall where his office waited with its uncomfortable chairs and its motivational posters about not caring.

Gabriel decided he’d keep the business. San Francisco would always have people who needed permission to set boundaries, and he was good at giving it. But maybe he’d add a new service. Helping people figure out the difference between healthy helping and codependent fixing. He could charge less and worry more, which seemed like a reasonable trade.

His phone buzzed again. Another client requesting emergency non-help. Gabriel looked at the message and smiled.

“That’s your problem to solve,” he said out loud, then deleted the text without responding.

Jon Negroni is a Puerto Rican author based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He’s published two books, as well as short stories for IHRAM Press, The Fairy Tale Magazine, and more.

Author’s Note

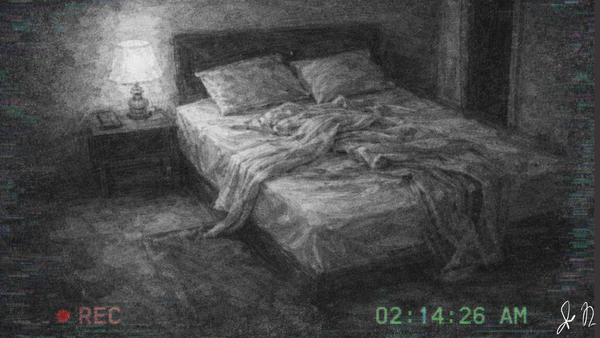

I was reading Codependent No More for a book club when the phrase “that’s your problem to solve” splintered its way into my head. At first, I thought it was just another boundary-setting mantra; simple, catchy, destined for a needlepoint pillow or Etsy print, etc. But then I was driving through San Francisco and passed a converted nail salon that now advertised something related to wellness. I remember the peeling acrylic letters, the ghost of a salon sign still visible beneath it. And I thought, what if the person inside that building was doing the opposite of helping? What if they charged people five hundred dollars an hour just to not care?

By the time I hit the next red light, Gabriel Hayes existed. By the time I got home, I had the opening line.

Like a lot of people, I’ve wrestled with the impulse to over-care. To try to fix, manage, or interpret other people’s pain instead of sitting with my own. Codependent No More calls that impulse what it is: a survival strategy that eventually becomes unsustainable. Gabriel is what happens when someone tries to turn that survival strategy into a business model, and I wanted to satirically chart what happens when this fails in the most human way possible.

This story isn’t meant to offer answers or perfect therapy advice or anything like that. It’s just a stopgap to the messy middle of recovery. And the uncomfortable truth that helping and being helped are equally vulnerable acts. And to the strange, slow alchemy that can happen when two people agree to stop performing wellness and start practicing connection.

Also, to be clear: I’m not opening a radical non-help coaching service. But if I did, the chairs would absolutely be uncomfortable on purpose.

Thank you for reading Cetera. Subscribe for free to receive new stories every week, right in your inbox. And if you have a few extra seconds, please consider sharing this story with a friend who might like it.