The Archivist

When missed calls and broken promises begin piling up as literal objects in his home, Isandro must choose to burn or keep everything he's been carrying for years.

To return home is to admit that the night has taken something from you, that the morning will demand an accounting.

Isandro’s collar contains the ghost of other people’s perfume, mixing with his own sweat and the smoke machine glycerin he has to endure during every music set. His ears still ring with bass, the frequency sure to live in his chest for hours, if not days. Four in the morning and Oakland sleeps outside his window, except for the rain, which never sleeps, only hurries against the glass like it’s trying to get in.

He sets his exhausted, expensive child of a bag down careful. The vinyl inside shifts, the plastic-on-plastic sound that means you carried us all night, we carried everyone else.

Isandro stops. His eyes settle into the light. The geography of home has changed.

There’s a woman sitting at his kitchen table, and she wasn’t there when he left. She has a clipboard. She has a DMV face. Or an emergency-room-intake-nurse face, he’s not sure. He can just tell that she is professionally present. Yet emotionally elsewhere. There are objects on his table that don’t belong to him, except.

Except they do.

Mijo, his abuela would say, there are visitors and there are visitantes. Visitors and guests. This woman is neither.

“I’m here to catalogue,” she says, staring at a cassette tape labeled Dad: 2002 Missed Call and a mug that says Didn’t Text Back: Pride, 2019 and a stack of birthday cards that read Never Sent: 2015-2023. Isandro never labeled these items.

“Lady, it’s four in the morning. And you’re in my house.”

“These items belong to you. I’m simply organizing them.”

The rain picks up in declaration. Isandro considers the taser in his bag, also his phone, also the tennis racket by the door. But she’s holding her pen like a nurse. Violence doesn’t suit her.

“Get out.”

“I only catalogue. I never deliver.”

“I said get out.”

She looks up then, and her eyes are the color of filing cabinets, a grey that reveals nothing. “You can’t move any of these items until you understand them. An absence accrues interest the longer it is excused.”

A hoodie appears. It materializes the way morning materializes, gradual then sudden. Damp. Size medium. The shade of green Julian always wore, the shade between forest and sage. The tag reads: Didn’t Show: Julian, Tonight.

“That’s not. He didn’t. We didn’t have plans.”

The woman makes a note. “You asked if he wanted to come hear you spin. He said maybe. You said cool, no pressure. You meant please come. He heard no pressure. The absence in question was born at 10:48 p.m. when you looked at the entrance for the fourth time.”

The hoodie, or "absence," isn’t damp, actually. It’s the light from the rain, playing shadows across it.

“Leave,” Isandro says. His voice cracks. “Please, for the love of god, leave.”

The woman stands, places a metal filing drawer on his counter. The label reads: A—Absences (Personal). “I’ll return tomorrow evening. We have more absences to sort.”

After she’s gone, Isandro stands in his studio listening to the rain argue with itself about whether to become a storm. The hoodie, somehow damp again, drips onto his floor, making a puddle that looks like the shape of something almost said.

Morning comes anyway, uninvited but inevitable. Isandro runs Lake Merritt because running is what he does to tell himself he must exist. His feet know the path, the goose shit and eucalyptus all, the lake he likes to call an ambitious lagoon. Other runners pass him, their absences trailing behind them in taunting silhouettes: Didn’t call mom back, Skipped the funeral, Meant to visit.

He can see them now, these absences, these little subtitle closed captions.

At the Fruitvale art space, Monica’s setting up for the workshop he’s supposed to help with. She’s running on activist coffee like any good artist.

“You look like shit, Sandro.”

“Didn’t sleep.”

“Again?”

He doesn’t answer. A teenage kid walks in carrying a bass guitar and a tote bag with words on it: Dad: Didn’t come to the recital, said he had to work.

“You good?” Monica asks.

“Yeah.”

Lied to Monica: Sunday morning, something in his pocket murmurs.

By the time he gets home, the absences have multiplied. They spill from his studio into the hallway. A bus seat labeled Left Early: Cousin’s Graduation. A takeout bag: Canceled Plans: Kept the food. And blocking his door, orange and sticky like hazard cones, a crate the size of a loveseat: Five Months of Excuses (Love).

The orange is the exact shade of a notice the city puts on a door before they condemn the building. It means: last warning. He tries to push it but can’t. Tries to climb over, but it grows.

“Move nothing until you know its origin,” the woman says. She’s back, wearing the same clothes, carrying the same clipboard, like she never left or like leaving and arriving are the same thing to her.

“I can’t get into my own apartment.”

“Then you understand the problem.”

The crate sweats overripe fruit and latex paint, the smell of trying too hard. He knows it well. It’s Ray’s smell, from when he would show up in the middle of the night with apologies and plans for trips they’d never take. Isandro tries to talk to the woman with a look. He doesn’t have words for what he’s feeling.

The woman opens a red ledger. “Every line on this is a debt. Every debt has interest. The math of absence works like this: one missed dinner becomes two becomes a hollow space where a relationship used to live.”

She pauses as if waiting for Isandro to respond. He only shrugs.

“Three choices,” she says next. “Burn, Keep, or Return to Sender.”

“If I choose wrong?”

“There is no wrong. There is what you live with and what you don’t.”

Afternoon light invades his windows in Oakland gold. Painter’s tape on his floor: three zones. Burn by the window. Keep by his record collection. Return by the door. The woman sits at his table, marking her ledger while he sorts.

A harmonica labeled Didn’t learn: Promised myself, 2018. That goes to Burn.

A photo album: Didn’t look: Mom’s last years. Keep, but turned face-down.

A voicemail nobody left because nobody called: Your birthday: Various, 2019-2025. He holds this one longest, this absence of an absence.

“On birthdays,” he tells the woman, “you’re not supposed to ask for anything.”

“And yet.”

“And yet.”

He makes café con leche, the way his mother taught him before she became an absence that sits in the Keep pile, too heavy to lift. The woman drinks hers black, no sugar, which figures.

Next, the birthday card from his father (never sent, never intended). Then the lunch plans with his brother (canceled for good reasons, bad timing). There’s the therapy appointment (skipped because healing felt too heavy that week). And there’s the biggest entry in the ledger, written in his own hand: Self: Years You Didn’t Want.

“What’s this?”

“The years you made yourself small so others could feel big.”

A text comes through. It’s David from the collective: Ey bro, checking in. Monica said you seemed upset about something. Need help with anything?

Isandro stares at his phone, trying to read its new language. He types: Actually, yeah. Can you come by? I have some stuff to move out and could use a hand.

David shows up twenty minutes later with work gloves and no questions. They move objects in silence. David doesn’t ask why there’s a piano bench labeled Didn’t practice: Promised Mom. He just helps carry it to the Burn pile.

“Next weekend,” David says when they’re done, “we’re doing the community meal. You should come.”

“I’m always there. I help cook.”

“No, I mean you should as a visitante. Let somebody else cook for you.”

After David leaves, Isandro’s hallway is clear. He takes a breath that goes all the way down. Reminds him that his lungs are just fancy bags.

The city notice arrives Thursday morning, stuck to his door with adhesive that means business: Violation of Housing Code 14.23.5: Excessive Personal Property Creating Hazardous Conditions.

The rain comes back, too.

Monica texts: Where are you? Event starts in an hour.

He’s promised too much again. The workshop, the community dinner, the DJ set this weekend. His calendar is a list of future absences waiting to be born.

“I can’t,” he texts back.

“What’s going on?”

“I need help moving some stuff.”

She cancels the workshop and shows up with two people he barely knows, including the new neighbor from 4B whom he’s only nodded to in the hallway. They arrive with boxes and contractor bags. Like David, they’re not full of questions, save for one or two from Monica.

“Jesus, Sandro,” she says, surveying the landscape. “How long you been a hoarder?”

“Whole life, apparently.”

The woman with the ledger watches from her corner, making notes as they work. She’s got a new category now: Warm Absences. These glow when he makes excuses for people. They pulse when he says “It’s fine” or “No worries” or “I understand.”

“Warm absences,” the woman explains while Monica and crew work, “tend to multiply when fed with appeasement.”

“So, what, I’m supposed to be an asshole?”

“You’re supposed to be honest.”

The neighbor from 4B, whose name turns out to be Kenji, finds the recliner-shaped shadow in Isandro’s closet. The tag reads: The Night He Didn’t Come Home: Dad, 1995.

“This one’s not moving,” Kenji says.

“Leave it,” Isandro says. “It’s been there thirty years, what’s another day?”

The woman stands, walks over to the closet. “Sign here, and all of this disappears. Clean slate.”

“Seriously? What’s the catch?”

“Erasure is possible at the cost of memory.”

Memory.

His father is worth about a thousand small absences that preceded the big one. Isandro’s absence is inherited, passed down like genetics. Isandro is just another Puerto Rican man trying to escape.

“No,” he says. “I’ll keep it.” He takes out his phone, sends a group text: Tomorrow night. Dinner party at mine, 7pm. If you’re coming, come. If not, that’s an answer too. It’s last minute. But I want you there.

Two of the Warm Absences in the corner immediately cool, turn to ash, and disappear.

Friday night and the rooftop has been transformed. Kenji brought a steel drum for burning. Monica strung lights. David hauled up speakers. No rain, except for maybe in the clouds. The Burning Night, Isandro calls it in his head. Seven people show up out of twenty-five invited.

“The rules,” the woman announces, standing by the fire drum, “are simple. Read the tag aloud. Then make your choice.”

Isandro starts small. A ticket stub: “Didn’t go: Jazz festival, 2019.” Into the fire. A set of keys: “Didn’t move in together: Scared, 2017.” Into the fire.

The group helps. Monica reads tags when Isandro’s voice breaks. Kenji tends the fire. David pours mezcal into small cups, the good stuff. Then comes the recliner-shaped shadow. It takes four of them to carry it up from the closet.

“The Night He Didn’t Come Home,” Isandro reads. “Dad. November 8th, 1995.”

The shadow weighs what a four-year-old boy weighs when he sits by the window until dawn and smells Lucky Strikes from somewhere he can’t see.

“He said he was getting cigarettes.”

We waited, the shadow whispers. We turned every car sound into his car.

His phone rings. Unknown number. Everyone goes quiet until it rings a third time. “You gonna answer?” Monica asks.

Isandro looks at the phone for one more ring. He silences the call. “Help,” he says, and seven pairs of hands help him lift the shadow. It resists, then surrenders, then becomes light enough to carry. Into the fire it goes, transforming into smoke.

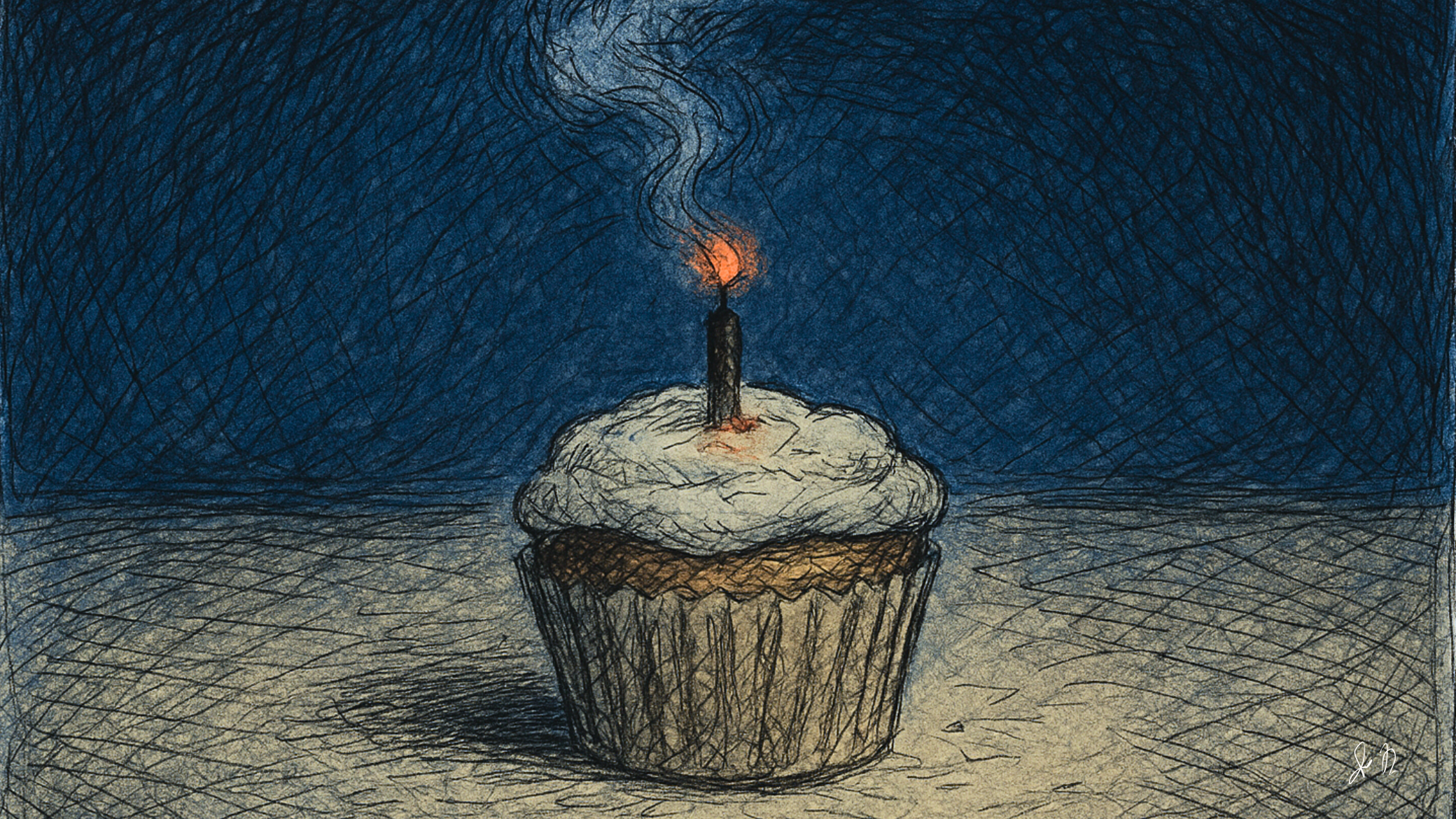

He pulls out one more thing: a grocery store cupcake, stale, with a candle. The tag reads: Didn’t Celebrate Yourself: 2015-2025.

“Happy birthday to me,” he says, lights the candle, makes a wish, blows it out, tosses it into the fire.

The rain returns, gentle now. The fire hisses, sends up steam with a crisp odor.

Isandro’s studio has windows open for the first time in months. On his bookshelf, where the woman’s filing cabinet used to be, sits his abuela’s photo and a matchbook. The matchbook says: For Future Absences: Use Wisely.

He’s cooking for himself instead of reheating takeout. Arroz con gandules, just like abuela’s but with his own twist. The kitchen is thick with the smell of sofrito, a perfect alchemy of cilantro and garlic that means someone is taking care.

The woman sits at his table, but her clipboard is closed. “I attend only by invitation now,” she says.

“You’re invited to eat.”

“I don’t eat. I catalogue.”

“Not today.”

She looks like she’s resisting a smile. “Absence is one thing,” she says, “But presence,” she pauses, looks at the pot on the stove, “presence is tricky, too.”

“So you’ll always have work.”

She stands to leave. At the door, she turns. “The matchbook has three matches. Use them wisely.”

“For burning?”

“For lighting. There’s a difference.”

After she goes, Isandro sits at his table with a bowl of rice. He texts the seven from last night: Dinner here Friday. 7pm at mine. I’m cooking family recipes. If you come, you come. If not, I want you there, anyway.

Monica responds first. “I’ll bring wine.”

Kenji. “I’ll bring dessert.”

David. “I’m there.”

The last text he sends is to Julian. Friday. Dinner for friends at 7, my place. If you come, you come. If not, I want you there, anyway.

He doesn’t wait for a response. Instead, he sets the table for eight. One spot for each person who said yes. One spot for whoever needs it. One spot for himself.

Author's Notes

This story came from thinking about absence as a tangible thing. We usually define absence as a vague "lack" of something. But I like to think of it as its own presence that accumulates and demands attention. We all carry these invisible catalogs of things we didn't do, didn't say, didn't follow through on. So I wanted to explore what would happen if those absences became visible. If they had weight and volume and demanded to be sorted.

The Archivist herself emerged as this figure who's neither villain nor savior, but something more like an accountant of the heart. She doesn't judge Isandro's choices; she simply makes them visible and asks him to take responsibility for them. That felt more honest to me than a story where someone swoops in to fix everything.

Magical realism works best when the fantastical elements serve the emotional truth of the story. The absences (the hoodies and voicemails and shadows) aren't just weird for the sake of being weird. They're external manifestations of internal realities that most of us recognize. We've all felt the weight of the call we didn't make, the relationship we let drift away through neglect. To get my point across, I had to stretch believability a bit while still using common anchors like clothing and life milestones.

What interested me most, though, was the community aspect of the story, which came about more organically as I drafted it. Isandro's healing doesn't happen in isolation, which is ironic because I specifically made him a DJ. Someone who works "solo" but is technically surrounded by a huge community that he has no direct connection with beyond the sound he's making. Nevertheless, community happens to him anyway the second he invites people in and they graciously help him carry the weight of what he's avoided. David, Monica, Kenji, they all show up without demanding explanations. That felt true to how real healing works, and as an introvert, that's the part of the story that codes utter horror for me, and I'm only half-joking.

The burning ceremony was inspired by a real thing, by the way, called the Burning Bowl Ceremony (or Burning Bowl Ritual). I've never done it myself, but the idea is pretty much what you just read, where people literally burn representations of what they want to release. But I wanted to complicate this real-life thing a little. Not everything gets burned, after all. Some absences, like Isandro's father's abandonment, become smoke that transforms rather than disappears. In other words, some hurts don't truly vanish. They just change shape. (To be clear, this story is not reflective of my personal experiences with my dad and other family members!)

I wrote this during a period when I was thinking a lot about the difference between being alone and being lonely, between solitude and isolation. Isandro discovers that presence—real presence—is actually harder than absence in some ways, because it requires vulnerability and the risk of disappointment. I know it's a heady one and maybe bit more experimental for what you might expect from me if you're familiar with my other work, but I appreciate you making to this little short story dinner party of mine. I forgot dessert, though.

Jon Negroni is a Puerto Rican author based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He’s published two books, as well as short stories for IHRAM Press, The Fairy Tale Magazine, and more.

Support Cetera

Paid members get exclusive perks like bonus stories, the ability to comment, and more. Plus you'd be helping us keep the bills paid. You can check out the subscription tiers below, or you can leave a one-time tip if that works better for you.