The Caller isn't Human

At 3 AM in a dead-end laundromat, the payphone rings three times. No one ever answers. No one ever should.

The rain never stops in this part of town. It runs down the window in slow streaks, turning the neon from the liquor store across the street into a pulse of blue and red. Inside the laundromat, the lights buzz in uneven time. The machines breathe heat. Ray sits behind the counter, watching the reflection of the door in the chrome of the dryers. Every thirty minutes, the payphone outside rings three times and stops. Nobody answers. Nobody ever has. The sound just folds back into the hum.

HUM

At 2:11 a.m., a light at the far end of the room flickers and steadies. The kid doing laundry for his three younger siblings is on his phone and doesn’t look up. The nurse folds her last pair of scrubs. Ray reaches for his coffee and freezes halfway, eyes on the door. The reflection isn’t right. He counts two people inside, but there should be three.

Ray stands up and sees the trucker still on the bench, hat over his face, one boot off, the other planted like he fell asleep mid-lace. The kid’s phone freezes, his thumb tapping a dead screen that mirrors the ceiling glare. The nurse stacks her bundle into a bag and bites her rubber wedding ring once, out of habit, then lets it snap back.

“Teena,” Ray says, because he knows most night people by name. “Rain’s picked up.”

Teena nods and leaves without speaking. Her tires hiss off into the steady wash. The door settles. The hum fills the space she leaves behind.

The payphone rings three times. Stops.

Ray looks at it until the reflection stops vibrating in the glass. Then he watches the floor where the water gathers in the mat’s low places. The mop leans in the corner. He tells himself to check the coin trays and the lint screens, and he does, moving down the line, opening and closing the small doors.

RING

2:40 a.m. The kid’s phone wakes up, then dies again. He shakes it once and pockets it. He moves to the vending machine and studies the rows as if the choice matters more than it does. He picks crackers. The spiral starts and stops halfway. The bag hangs by a corner and doesn’t fall.

“Tap the glass near the bottom,” Ray says. He doesn’t raise his voice. No need.

The kid obeys and the crackers drop. He says thanks. He doesn’t eat the crackers. Probably saving them for home.

Outside, a car rolls by with one headlight. It pushes water and disappears. The payphone glow is weak but it holds. The booth’s bulb has been failing for months, but it never quite gives out.

The door opens and Officer Dyer steps in, rain on her shoulders, hair in a frizzy bun. She nods once to Ray, once to the kid, then looks at the sleeping trucker and the clock on the wall.

“Coffee?” she asks.

“Stale,” Ray says. “Can’t afford the good stuff anymore.”

“That’s fine.” Dyer pours her own into a paper cup and doesn’t add anything to it. She stands, sipping, facing the door like it might decide to change its mind. The radio on her shoulder murmurs, then clears, then goes back to a low hiss. She thumbs the knob and lets it be.

“You hear the payphone tonight?” Dyer asks without looking at Ray.

“Twice,” Ray says.

“Anyone answer?”

Ray shakes his head. “Never.”

Dyer chuckles and watches water score the neon into lines. “Well, somebody’s paying that bill,” she says.

The trucker snorts awake, repositions his hat, and falls back down into sleep without opening his eyes. The kid stands by the door and tries to get a signal. He raises the phone and turns like a weathervane. The screen stays black.

At 2:58 a.m., the payphone rings again. Three times. It stops in the middle of the third and starts over like the signal stuttered. Dyer sets her coffee down, crosses to the door, and peers out through the glass.

“You want me to—” Ray starts, but Dyer is already pushing out into the rain.

Ray watches her go to the booth. Dyer lifts the receiver and listens. Her face doesn’t move. She looks left, then right. She says something short that the wind eats, then holds the receiver away to look at it, like the plastic could tell her more if she stared at it harder. She puts it back gently and comes in with rain knocking off her jacket in small taps.

“Dead air,” she says. “Could be kids.”

“Kids aren’t out,” Ray says.

“Kids don’t sleep,” Dyer says. She tastes her coffee and winces. “Stale it is,” she says, and smiles.

Ray goes back to the coin trays. Dyer walks the rows slow and casual, but her eyes catch edges. The door’s reflection sends lines into the chrome. If someone stood outside, centered with the phone, they’d be a cut-out figure in the glass. There’s no one there. Just rain, the liquor store, and the outline of the booth.

The kid moves to the bathroom. The lock doesn’t catch; never has. The door sits in the frame, keeping the night out.

At 3:07 a.m. the light at the back flickers twice and steadies. Ray hears something under the hum, a thin scrape like rubber on tile. He looks at the mop and tells himself that’s all it is. He listens harder and hears the scrape again. It has a rhythm to it: two steps and a pause, then two more. The noise stops when he stops. He breathes through his mouth until the hum fills whatever space the sound left behind.

The bathroom door opens a crack. The kid sticks his head out. “Hey, the faucet won’t shut,” he says.

“The cold makes it stick,” Ray says. “You have to turn it extra.”

The kid nods once and disappears. The water keeps running for a beat, then stops with a cough of pipe.

Dyer’s radio breathes static in and out. A voice tries a sentence and falls apart halfway. She thumbs the dial again.

“You ever lose power?” she asks.

“Not all the way,” Ray says. “Just the back row. When it does, it comes back the way it went. One after the other.”

Dyer looks at the dead bulb in aisle three. “You need a ladder,” she says.

The payphone rings. One. Two. Three. It stops. Dyer doesn’t move. Ray doesn’t either.

WASH

At 3:19 a.m., a delivery truck noses into the lot and angles toward the alley. Lin steps in with a plastic tub of detergent packs, shakes the rain off her hat, and sets the tub on the counter.

“You’re light on lemon,” she says.

“We never sell lemon,” Ray says.

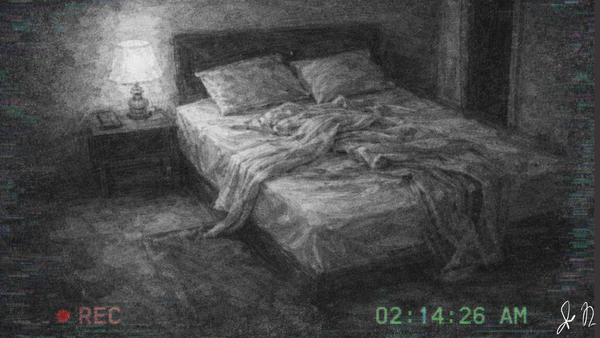

“Then you’re heavy on everything else.” Lin signs her own clipboard. She looks past Ray at the wall of monitors that show the cameras. The pictures swim. One image stutters as if the lens is breathing. The alley cam is a gray smear. The door cam shows the payphone booth in black and white, its bulb brighter than the real one. “You got ghosts again,” Lin says, like it’s a joke that’s been told before.

“Just rain,” Ray says.

Lin whistles at the sleeping trucker, who doesn’t wake. She holds the whistle, one long note, and smirks at Dyer. “Test,” she says. Dyer doesn’t return it. Lin winks at Ray instead. “You hear about the guy down at the water plant? Says he keeps hearing the same song on the loudspeaker no matter what station he sets. Same chorus, over and over. Whole place is out of time.” She lifts the tub, rotates it like she’s testing the weight, then sets it down. “Anyway,” she says, which is a way of saying none of that matters here.

Ray signs the slip. Lin points a finger at the monitors again. “That alley looks…” she starts, then waves it away. “I’m late.”

She goes out. The door closes. The alley cam clears for a second. It shows nothing but a glistening rectangle of wet concrete and a dark line that could be a shadow or not. Then it goes grainy again and stays there.

The trucker snores. Dyer finishes her coffee because there isn’t anything else to do with it. The kid comes out of the bathroom and uses the hand dryer, even though his hands don’t look wet. He keeps them under the blower until it times out, then presses the button again. He repeats it one more time before finally stopping.

The payphone rings again. Three times. On the third, the booth light pops and goes dark, and the ring keeps going for half a second after the bulb blows. Ray feels the ring come through the glass more than he hears it.

Dyer moves to the door. She keeps her hand on the handle without opening it. She steps out into the rain and crosses to the booth. She tries the receiver. She touches the bulb housing with the back of her hand. It’s hot.

Ray watches her come back in. Dyer’s shoulders are drenched again and her bun is about to give up. “Bulb’s gone,” Dyer says. “Phone’s dead. Felt hot, though.”

“Short,” Ray says.

“Or not,” Dyer says.

The kid goes to the vending machine again and buys the same crackers. This time they fall all the way without sticking. This time he opens the bag and eats one, slow chewing, watching the monitors like they’re a window into a better room.

Ray takes the tub of detergent packs into the back to shelve it. The door doesn’t latch behind him. He sets the tub down and stands still for a second. The smell is stronger back here, almost like wet paper. He hears the scrape again—two steps, a pause, two more. It might be the drip from the water heater hitting the concrete in a rhythm that isn’t random. He lifts his head and listens. The drip stops. The hum keeps going.

When he comes out, the trucker is gone. The bench is empty except his hat now sits on the seat. Ray looks at the bathroom door. It’s open. He looks at the dryer row. The last machine on the left has stopped early, clothing inside pressed against the glass like a face. He moves down the line with his hand away from his side like he’s ready to touch something hot without thinking.

“Where’d your guy go?” Dyer asks without turning fully around.

“Bathroom maybe,” Ray says.

Dyer nods and walks over. She taps the bathroom door. “Sir?” she says. No one answers. She pushes the door enough to see tile and a sink and a mirror that reflects a bulb that doesn’t flicker. She steps in and looks behind the door and under it. She flushes the urinal just to test the plumbing, then steps out and shakes her head. “Not in there.”

The kid points at the monitors. “He went out,” he says. “I saw the door.”

Ray rewinds the feed with the cheap metal jog knob. The door cam breaks into frames. The trucker stands up, puts his boot on, hesitates, then moves toward the door without looking at anyone. He disappears into the edge of the frame. The payphone booth is dark. The rain looks like lines etched onto the glass.

Dyer goes out again. The lot is empty. The truck cab is still there. The engine isn’t running. The trailer door is locked. Dyer taps it anyway and waits to feel movement through the metal. There’s nothing. She looks at the booth, then past it into the mouth of the alley. The dark line the camera showed is still there. Up close, it’s just a stripe where water isn’t pooling because the concrete dips. She reaches down and touches the seam. It’s dry. She pulls her hand back and wipes it on her jacket without meaning to.

She comes back in. “Could’ve taken a walk,” she says. “People do.”

“At three in the morning?” the kid asks. It comes out like he didn’t mean to say it. “In this rain? Without his hat?”

“People do weirds things at three in the morning,” Dyer says.

Ray nods. Not like he has a better answer. He goes to the back door to check the bolt. It’s slid all the way. The metal is cold.

QUIET

At 3:41 a.m., the power in the back row flickers off, then on, then off again. It steps down in sequence, one machine, then the next, like a person is walking along the line throwing switches only they can see. Ray feels the air change, a small drop in pressure like a door opened somewhere behind the building and stayed that way. The hum shifts and refuses to settle.

Dyer lifts the radio. She speaks into it, says her location, waits for the click and the answer. The answer comes thinned out. She tries again. The radio carries her own voice back to her a second late. She clips it back to her shoulder and doesn’t show her teeth when she breathes.

The kid stands in the middle of the floor with his empty cracker bag in one hand and the dead phone in the other. He looks at the booth outside. He looks at the door handle. He doesn’t touch it.

A janitor named Walt comes in from the adjacent office building with a wet trash bag and a face like he’s been awake too long in bad light. He nods at Ray and at Dyer and gives the kid a half-smile. “We losing juice?” he asks.

“Back row,” Ray says.

Walt points his chin at the ceiling. “Ballasts. They hum before they go,” he says, then shrugs. “Everything hums before it goes.”

He crosses toward the bathroom with his bag and his long-handled grabber. He doesn’t lock the door. He never does. He whistles something tuneless and stops halfway through when he hears himself. The hand dryer spools up and dies on its own. Walt chuckles, soft.

The payphone rings. Three times.

Everyone looks at the dead booth. The bulb is out. The ring is loud anyway, not dulled by glass, bright in the room as if it isn’t coming from outside at all. Walt freezes in the bathroom doorway with his hand on the frame. He turns his head without turning his body and looks back at Ray.

“You getting that?” he says.

Ray doesn’t answer.

The ring stops. The hum takes its place. The kid sets the empty bag on the counter carefully, like he doesn’t want to make a sound louder than that ring.

Walt goes into the bathroom. The door rests in the frame. It doesn’t latch. A beat passes. Another. Water runs for one second and shuts off with a cough again. The hand dryer spools up, then down. Walt doesn’t whistle. Ray glances at the monitors and then away. He tells himself not to. He looks back anyway. The bathroom camera shows the sink and the mirror and the paper towel dispenser that only works after two tries. The angle doesn’t show the stall. The sound doesn’t carry. The picture holds steady.

“Walt?” Ray says, not loud.

No answer.

Dyer moves toward the bathroom. She pushes the door with two fingers. “Walt,” she says, and steps in.

The kid breathes through his nose.

Ray stares at the door and counts without meaning to. He gets to eight and the door swings wider. Dyer comes out. She stands in the doorway longer than she should. She doesn’t say a name. She doesn’t say “Jesus” or “no.” She looks at Ray and then past him at the booths on the monitors and then back at Ray again. “Call his number,” she says.

Ray moves to the phone behind the counter and picks it up. The dial tone is a flat line that isn’t a tone at all. He sets it down and tries his cell. It hangs on searching and doesn’t find anything to search. He looks at the payphone outside, dark as a dead tooth. He thinks of lifting the receiver and doesn’t move.

Dyer turns and closes the bathroom door until it rests. She doesn’t shut it. She doesn’t want to trap the air inside. She steps to the counter. “We’re on our own for a minute,” she says. “Nobody go outside.”

The kid nods like a person in a first-aid video.

“Where’s the trucker?” Dyer asks Ray, as if asking now will change the answer from before.

“Gone,” Ray says.

“Where?” Dyer says.

Ray doesn’t answer.

The back row of machines goes off, one, two, three, four, but not in order. The pattern is wrong. The hum deepens until it feels like something under the floor is breathing different from what’s above it. The dead bulb in aisle three flickers and holds for a second, like it remembered it should be on, then lets go.

The door handle moves. No one is touching it. The handle goes down a quarter inch and stays there like a finger weighing it, testing it. It lifts. It goes down again. Dyer aims her eyes at it and doesn’t look away. She steps toward the door, slow.

“Don’t,” Ray says, and it is the only word he has said with any force tonight.

Dyer stops. The handle clicks just enough to sound like a lock engaging and then not. The payphone rings.

One.

Two.

Three.

The fourth ring climbs into Ray’s skull and hangs there. Dyer’s face doesn’t change, but Ray sees the muscle at her jaw jump once. The ring doesn’t stop. It extends. It’s not a ring anymore, not really, just a tone that doesn’t belong to any machine in the building.

Something knocks politely on the glass.

Dyer speaks to the door. “Place is closed,” she says, as if testing whoever’s on the other side.

The handle lets go on its own. The knock doesn’t repeat. The tone fades out like it decided to, not like it got cut.

“Back room,” Dyer says. “Bolt it. Now.” Ray moves. The kid doesn’t move until Ray points and says “Go,” and then he goes. Dyer stays by the door and watches the reflection hold steady in the metal trim. She sees herself as a silhouette. She sees the booths as blocks of cheap wood. She does not see anyone else, and that is not enough to make her open the door.

The back room is smaller with the three of them in it. The bolt slides. The room changes temperature even though the thermostat doesn’t. Ray points at the breaker panel. “Back row,” he says.

“Leave it,” Dyer says. “Dark is better.”

“Not if it’s in here,” the kid says, and then he looks down like the words got away from him.

They stand in the quiet that isn’t quiet. The building keeps breathing. The water heater clicks. The compressor starts and stops twice without settling. The monitors in here show the same bad pictures as the ones outside. The bathroom feed holds the mirror and sink. The door inside the frame moves with the wind.

Dyer’s radio coughs and says her own name in a voice that could be hers. She turns it off. She turns it back on. She doesn’t try again.

“Guess we wait,” she says.

“What for?” the kid asks.

“For it to pass by,” Dyer says, and it sounds like she has said this before in other places for other reasons.

The bolt turns on its own.

It doesn’t slide all the way. It twitches, a notch, as if someone is trying to understand how it works by touching it. Dyer puts her hand on it and holds it in place. Ray looks at the floor. The line where water should collect stays dry. He follows it with his eyes to the far corner where the mop is. The mop handle leans and then straightens without falling.

“Tools,” Ray says, and opens the cabinet for the breaker lockout bar and the long screwdriver that isn’t for anything in particular. He hands the bar to Dyer and the screwdriver to the kid.

They stand with their backs to the wall and the door in front of them. The bolt stutters again, then stops, like whatever is on the other side lost interest or learned all it needed to know.

Dyer’s watch says 3:59 a.m. It ticks once and doesn’t tick again. The second hand rests between seconds.

“No clocks,” Ray says, and he didn’t mean to say it out loud.

The kid laughs once. “It gets very bright at four,” he says, and Ray doesn’t know how he knows that.

The payphone rings. They hear it clearly in the back room with the door closed and the bolt half-slid. It rings three times. It waits. It rings a fourth time and stops half a beat before the sound should finish.

Dyer exhales. She lifts her hand off the bolt. She waits for the door to push. It doesn’t.

Ray opens the breaker and throws the back-row switches one by one. The lights come up in sequence, not the way they went out earlier, but in a clean line, like the building remembered the right order on its own. The hum finds its pitch again. The compressor settles. The water heater stops clicking. The second hand on Dyer’s watch doesn’t move, but the room feels like it decided to belong to them for a minute.

They open the back room door and step into the laundromat.

Walt is not in the bathroom. The door is open. The mirror is clean. There is a wet line on the floor where feet would walk if they didn’t lift, but it doesn’t lead to the back room or the front door. It stops in the middle of the aisle and does not resume.

The kid moves toward the bench where the trucker slept and stops himself halfway. Dyer goes to the counter and checks the monitors. The door cam is clear. The alley cam shows only rain. The bathroom cam shows what the bathroom looks like when no one is in it. Dyer touches the screen as Ray walks to the front windows. The payphone booth is dark. The receiver hangs straight, no sway. The liquor store neon across the street has shut off. The sign still reads LIQUO, missing the R the way it has for months, but now the letters don’t even pretend to light. The rain keeps falling with quiet velocity.

He turns to say something to Dyer and the kid. He doesn’t. Instead he listens. The building is very quiet now. The hum is steady and low and honest. He hears only that and his own breath and the click the door makes as the night adjusts against it.

The payphone rings.

One.

Two.

Three.

Four.

Ray doesn’t move. Dyer doesn’t either. The kid closes his eyes like he is about to lift something heavy.

The fourth ring ends in the middle again and leaves nothing behind, not even the hum for a heartbeat. The quiet is complete. It has weight. Then the lights continue their buzz, the machines breathe, and the laundromat returns to what it was.

They don’t open the door. They don’t answer the phone. They stand in the light and wait for the sound to tell them whether the world outside still wants them or not.

Author's Notes:

Our October of Horror continues, and this time we're publishing a story that aims to build dread through restraint and precision rather than explicit scares. Let's break down what's going on in this story.

First, the atmosphere. The laundromat serves as our liminal space, a place people pass through at odd hours, neither fully public nor wholly private. The 2-4 a.m. timeframe places us in what folklore calls the "devil's hour," when reality feels thinnest. The constant rain creates isolation while the broken neon sign (LIQUO missing its R) signals that things here are incomplete in small but persistent ways.

From there, I set out to provide meticulous attention to patterns and their disruption:

- The payphone rings exactly three times every thirty minutes...until it doesn't.

- Machines fail in sequence going one way, then return in a different order.

- The fourth ring that shouldn't exist but does.

- People disappearing not dramatically but simply being absent where they were present.

Through it all, Ray serves as our anchor. He's observant, methodical, and trying to impose order through routine (checking coin trays, counting). Officer Dyer represents failed authority. Her radio won't work, her presence can't prevent what's happening. The kid and the peripheral characters (Walt, the trucker, Lin, Teena) create a community of night people who understand unspoken rules about how to exist in these margins.

Which brings us to the threat's fundamental unknowability. We never see it directly, only its effects. Reflections show wrong counts of people. Door handles test themselves. The bolt learns how it works. There's a wet line on the floor that stops nowhere and leads nowhere.

The entity, or whatever it may be, seems to be studying, learning, and testing boundaries. Possibly without malevolence. It might just be an alien curiosity (which is somehow more disturbing).

For the prose, I chose to employ short, declarative sentences that accumulate weight in order to mirror Ray's methodical observation. The use of "HUM," "RING," "WASH," "QUIET" as section breaks should create a sense of mechanical progression while highlighting the story's focus on sound and its absence.

The recurring motif of things that almost work (the bathroom lock that won't catch, the dying phone booth bulb that won't quite fail, the vending machine that sometimes drops crackers and sometimes doesn't) creates a world where reliability itself has become unreliable. This is a hallmark of short-fiction horror writing when you don't have a lot of time or words to get the existential dread across.

To that end, the story obviously has zero resolution. The survivors don't escape or triumph or die or fall apart. They simply wait "for the sound to tell them whether the world outside still wants them or not." This suggests that whatever has been testing them isn't finished. Or worse, that they've already been changed in ways they don't yet understand.

The reason it ends like this is because at its core, this story is about the fragility of the systems we depend on. Not just electrical and mechanical, but social and perceptual. The working-class night shift setting isn't incidental, after all. These are people already living on the margins, already used to being unseen. When something else unseen arrives, they're both the most qualified to recognize it and the least equipped to stop it.

The title's declaration that "The Caller Isn't Human" is never explicitly confirmed in the text, leaving us to wonder if the real horror is that it might be something worse...or that it might be nothing at all, just the universe revealing its fundamental indifference to our need for coherence. Whatever breaks us down isn't always human. It's far bigger and scarier than that.

Jon Negroni is a Puerto Rican author based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He’s published two books, as well as short stories for IHRAM Press, The Fairy Tale Magazine, and more.

Support Cetera

Paid members get exclusive perks like bonus stories, the ability to comment, and more. Plus you'd be helping us keep the bills paid. You can check out the subscription tiers below, or you can leave a one-time tip if that works better for you.