The Morrow Twins

There had been three girls in the attic, once. Two names I knew. One I had burned.

The trees hated me. Or maybe it was the wind. Or the frost in the air that tried to mimic the texture of my grandmother’s breath when she used to say my name in the dark—Irenka, a name I shed like old skin when I left Greyport, Mass behind. When I stopped being hers. When I let my throat fill with Cambridge vowels and university syllables. But the trees were watching me now, bending low and splitting open their own bark. I should not have come back.

The road into Greyport was a tongue of black tar that led straight into the mouth of town. I drove it like a drunk fool, letting my foot off the brake just enough to slide into memory. My teeth chattered. Not from cold. I told myself I was here for the funeral.

Thalia Morrow was dead, you see. Drowned, it turns out. She had always been the kind of girl to love water the way a match loves gasoline. It suited her. It suited the town. And I was going to sit in a pew like a good girl and listen to someone pretend her death meant something. And I told myself I would not stay the night. I told myself I would not knock on the Morrow house door. But I did. And the house was the same as I remembered. These old Victorian things rot slowly, prettily. Paint peeled off the shutters in long, curling sighs. The screen door hung open like a mouth that had forgotten how to close.

I knocked. Once. Twice. The door opened. I saw her. Thalia. But not Thalia. A woman with Thalia’s coal-black braid. And crooked smile. And scar under the left eye—no, right eye. No, wait. That wasn’t right. Her mouth opened and something came out of it that sounded like my name.

“Iris,” she said.

But it wasn’t a voice. The sound was only in my head. My knees buckled inward like they wanted to return to the earth. I didn’t faint, but the floor leaned closer than it should have. I could smell soap. Lemon rind. Dust. Burnt sugar. Old sleep. Maybe she had only just woken up.

“I’m Tess,” she said, blinking. “I was Thalia’s twin.”

Twin? What twin… Wait, I remembered her. No, I almost remembered her. There had been three girls in the attic, once. Two names I knew. One I had burned.

“Tess,” I said, as if believing it.

The house swallowed me. That’s the only way I can put it. I certainly didn’t feel welcome. When I stepped over the threshold, something in the base of my skull began to itch. A nerve that remembers being pinched.

Tess walked ahead of me barefoot, and I saw the way her heel touched each floorboard with perfect sense, like she knew where they creaked, where they didn’t, where the rot lived under the carpet and where it was safe to step. She didn’t offer to take my coat. She didn’t turn around.

I smelled wet velvet, like something had died and decided not to leave. Though maybe it had. Maybe it was me. There were people in the parlor. Not people. Reflections of people. Local shapes. Greyport faces, slack and swollen from weeping. I recognized them in the way one recognizes a recurring dream. The pharmacist. The man with the missing finger. A girl I’d kissed behind the high school gym, who now had two children clinging to her knees like tumors.

No one looked at me. No one blinked. Not even when I sat down. Except Tess. She stood beside the casket, hands clasped. The body inside—I forced my eyes to it—was Thalia. Or enough of her. Waxed skin. Combed hair. They’d tried to cover the bruising at her temples with pink undertone. Her smile was glass. Her lips were stitched to a hush. She looked peaceful. Which was absurd. Thalia never looked peaceful. Not even when she slept. She had always been the girl who moved too fast, talked too loud, carved insults into bathroom stalls with a pocket knife she kept in her sock. She had never been still. Never sweet. I wanted to laugh. Or vomit. I cried.

Tess stepped forward. Her eyes found mine. She touched the casket, just the edge of it, and said, “I wish you hadn’t come.”

My spine folded inward. My brain played a chord. “Did I ever meet you?” I asked.

A stupid question. A coward’s question. But Tess smiled. “Only once,” she said. “I don’t blame you forgetting.”

I opened my mouth to speak. Nothing came out. Not even a scream.

I slept in the attic. Only room available, which I assumed was a lie. But either way, I had walked upstairs, halfway through the wake, and no one stopped me. Tess watched me go, didn’t say a word. I think I wanted her to. I think I wanted her to say not yet, or wrong room, or we burned that place down, remember? But she said nothing. She only smiled. That same smile. Like a door closing in reverse.

The stairs were dust-limned and shallow. Each step might’ve taken a year off my life. By the time I reached the top, I had aged back into my skin. Into the girl who used to play with poppets and dollhouses and whisper fake wedding vows into the cracks of the floorboards where I drew lines and circles with chalk. The attic was smaller than I remembered. Smaller and louder. I could hear the house breathing. A wet inhale through the vents. A pulsing under my feet. Something lived here, still. There was a mattress with no frame. Just the sad shape of sleep. I sat down. Then laid down. Then let the wood rise up and wrap around me. It was big, for a coffin. I closed my eyes. I didn’t sleep. I tried to remember what happened. There were three girls in the attic. One with black hair. One with dirty knees. One with no name. We had played a game again and again. The mirror game. The chalk circle game. The blood-and-breath game. We said the names out loud, like incantations:

“Thalia.”

“Iris.”

…

We paused. The third name was never said. Not fully. Not clearly. The third girl had whispered hers only once, but our laughs drowned it out. The third girl never laughed. Instead, she looked at us with a face that refused to finish forming. A sketch with the eyes smudged out. A photo trapped between two developing chemicals. And we went still. We never played the game again. Until now.

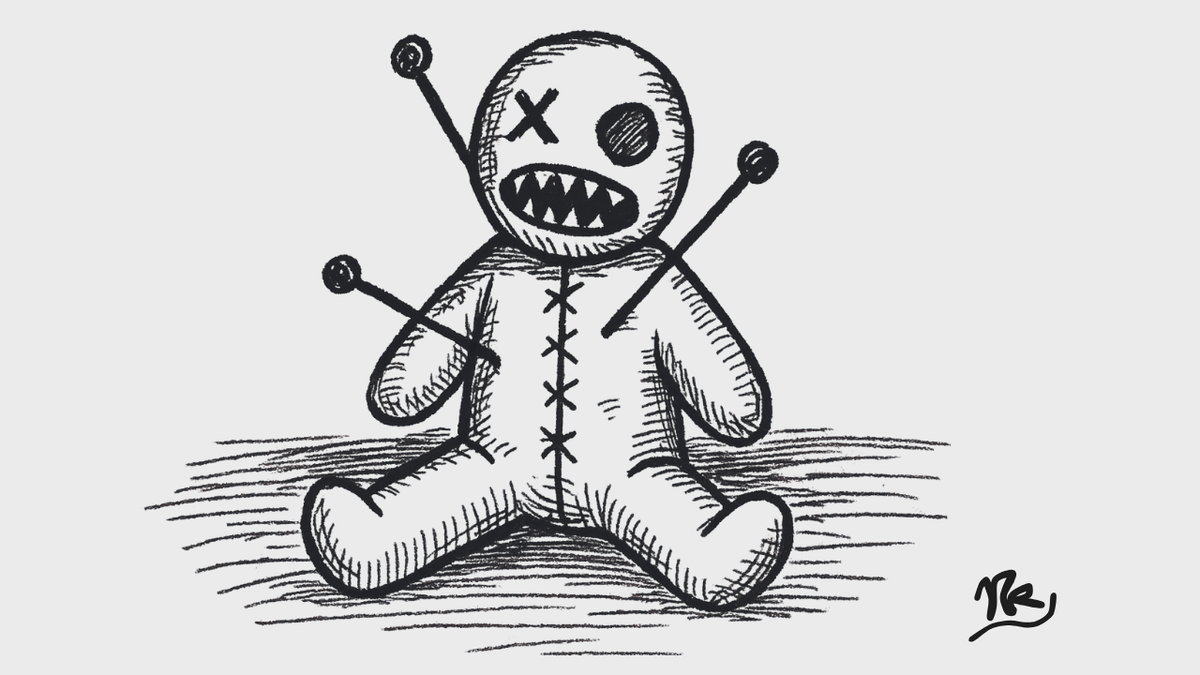

I woke up with my arms above my head. The mattress was gone. My wrists were bleeding. There were chalk marks on the walls in spirals and names. One of them mine, but written backwards. One of them Tess. And one of them unreadable. In the corner, Tess stood holding a poppet. A doll, sort of, with teeth.

“You used to know how to play,” she said with the poppet.

I tried to scream. I had no mouth. I tried again. No luck. So I ran.

I made it to the woods before I took a real breath. The air tasted different here. Clean, but still dirty. The trees huddled close, bramble-slick and rib-thin, as if they’d grown in the shape of a mouth. I didn’t have time to grab a coat, but at least the cold kept my thoughts sharp. I had to keep going. Stopped after a while for another breath and looked around. The path—the old one behind the school—still existed. That shocked me. So much else had rotted. But not this. The stone bench was still there, blanketed in moss. I sat on it, anyway. My fingers throbbed from where the poppet had bit me on the way down the stairs.

Last night. Last night. I didn’t dream.

We had come here once. Me, Thalia, and “Tess.” We’d brought a mirror. The small one with the cracked edge. The one Thalia said would bleed if you held it too long. We had dared each other to look into it and say what we saw. I’d said “I see you.” Thalia said “I see me.” The third had said nothing. Just stared and watched until we dropped the mirror.

I heard something shift beneath the leaves. A wild animal, hopefully. Tess had told me once—we were ten, maybe eleven, or maybe I imagined the whole thing—that the forest had a soul. And souls have memories. They don’t forget footsteps. Especially not the guilty ones.

“Are you real?” I asked the trees. I didn’t expect a response.

Something moved behind me. I turned. Tess stood at the edge of the clearing. She looked different. Her eyes weren’t the same shape anymore. Not quite Thalia’s. She held the poppet again, its teeth glistening with my blood.

“I thought I’d find you here,” she said. “You always ran here when you were scared.”

I didn’t remember that. But my body did. I stood up. My knees cracked. “I wanted to see if it was still here,” I said.

“It is.”

I nodded. “The games we played…”

“The games you forgot,” she said.

My mouth dried.

“We needed a third,” she said. “We always did.”

I stepped back. “I don’t want to play.”

“But we need a third,” she said, holding out the poppet.

I didn’t move. Not at first. But my hands stirred on their own.

The doll blinked.

I had no choice. I had nowhere else to go.

We walked back to the house without speaking. I couldn’t feel my fingertips. Maybe it was the cold, maybe it was the poppet. It rode inside my coat pocket. Every few steps I could feel its teeth shift, counting my ribs.

The door creaked open for us like it had been watching from the window. The inside smelled different now. Less mold. Tess led me to the parlor, which had been locked for years. We weren’t supposed to open it. Ever. The door was already open.

Inside lay three candles, arranged like a triangle. A ring of salt. Our names carved into the old floorboards, shallow and uneven. Mine had been added recently.

“I didn’t write that,” I said.

“I know,” Tess said.

The mirror stood on the mantle. Still cracked. My reflection wasn’t there. Only hers. Thalia’s.

“Sit,” Tess said.

I didn’t want to. But I did. She handed me the poppet again, and this time, it was warm.

“We never finished the game,” she said. “That was the mistake.”

“Mistake?”

“Thalia’s mistake. But she’s ready to play again.”

I shook my head. “Tess, she died.”

She looked at me like I was slow. “She was supposed to.”

The candles flickered. The mirror showed three girls now. Me, Tess, and the third. Older now, with my face but not my eyes. Her mouth moved, but no sound came out. Then mine moved too.

“Tess,” I whispered. “What did we call it?”

“We didn’t,” she said. “That was the problem.”

The poppet’s mouth opened.

Wind rushed through the parlor, though the windows stayed shut. Salt scattered. Wax bent. Something pressed against my back, cold and enormous. It whispered in no language I knew, but my bones knew. My bones answered.

And Tess said the words.

“Your turn.”

The mirror opened. Almost like a door. The crack became a wet seam splitting through everything I’d been trying to remember. We were in the attic again, but not the attic. Not how it was. The room was too clean, too perfect, like it had been painted from memory. Thalia stood in the center, barefoot, her dress hem drifting as if underwater. Her hands were pushed together like she was praying.

“Iris,” she said.

She used my name like it was hers to say. Like she’d earned it.

“Tess,” I whispered, but Tess wasn’t behind me anymore. Just the poppet, its teeth sunk into my palm, drawing blood like ink.

“You left me,” Thalia said. “You left before the game ended.”

“No,” I said, my voice cracking. “We—we didn’t know what we were doing.”

She tilted her head. “Didn’t we?”

The mirror pulsed. Behind Thalia, shadows bent into shapes—child-sized, hollow-eyed, grinning. They whispered nursery rhymes, all of them overlapping.

“I tried to come back,” I said. “I tried so hard.”

“I know,” she said. “And you felt bad. For a while.”

I stepped closer. My knees shook. I reached out. My hand passed through her shoulder.

“But I cared,” she said. “I never forgot you.”

And that was true.

I never forgot any of it. The attic. The circle. The words we said just to scare each other. How we drew blood from our fingers and fed it to the poppet, laughing. How the mirror cracked when Thalia spoke something that didn’t belong to her. How I ran, dragging Tess behind me. How Thalia stayed behind.

“You chose to stay,” I whispered.

“I became the third,” she said. “The one who stays. So you and Tess could be the ones who leave.”

“But we didn’t leave,” I said. “Not really.”

Her smile was small and tired. “Then let one of you go.”

The shadows swelled. Tess appeared at my side again, older than she should be, younger than she ever was. We looked the same now. Same hair. Same eyes. Same scar at the base of the chin from falling on the porch steps that night the mirror broke. But she didn’t bleed.

One of us had to stay. That was the rule. That had always been the rule. I looked at Thalia. I looked at Tess. I looked at the poppet. I dropped it. It vanished before hitting the ground. Right as it did, the mirror cracked again. This time all the way through.

Something shut my eyes by force.

I woke up in the woods. The stone bench beside me. Blood on my palm. A single candle burning at my feet, already half-melted. The house was gone. The parlor too. Only the mirror remained, lying in the grass. I picked it up.

Only one face stared back.

Mine.

I hope.

Author's Notes:

I normally don't write horror at all, and in fact, as Cetera Magazine's head editor, I've been working on a short story that is most definitely not horror for months as my debut piece. Alas, October rolled around, and we're celebrating by devoting the entire month to spooky stories of varying subgenres. For me, I just knew I had to do a gothic horror about twins, and I also got to try my hand at this week's original artwork.

That said, this is a gothic piece with a huge dose of psychological haunted house fiction mixed with Americana. The story takes place in the fictional town of Greyport, Massachusetts (originally Greymire, of which our cofounder Jon Negroni rightfully pointed out as sounding too "fantasy") and in my mind it's a merge of Newburyport and Salem. Part coastal town part f'd up history.

And there's something deliciously terrifying about twins, isn’t there? Two halves of the same soul, but also (potentially) two entirely different beasts. One good, one wicked. One brave, one crumbling. I’ve always been obsessed with the idea that no matter how much you try to outrun who you were as a child, someone remembers the truth of you. Especially a sibling. Even more especially your twin.

Like I said, horror isn't normally my cup of tea. But Iris is the kind of narrator I always love to write: skeptical, half-feral, way too self-unaware to unpack her childhood trauma. She walks (or drunkenly drives) into her old town like she’s just here for the funeral, but you know just like I did that she’s lying to herself. The house is inviting her back. The past wants her back. And some part of her wants to stay. That's the horror aspect I did find irresistible, even as someone who would've been driving myself to Canada the second after getting bit by a doll.

Thanks for reading my debut with Cetera and for supporting all of our work over the last nine months. Editing Jon and Will's stories has been an absolute delight while also solidifying my imposter syndrome, though their encouragement (along with staff reader Bridget Serdock's) has absolutely reinvigorated me as a fiction writer. Here's to more stories that go bump in the attic.

Natalia Emmons is the managing editor of Cetera Magazine and one of its cofounders. She mainly writes short fiction, poetry, and extremely long text messages about the perils of run on sentences.

Support Cetera

Paid members get exclusive perks like bonus stories, the ability to comment, and more. Plus you'd be helping us keep the bills paid. You can check out the subscription tiers below, or you can leave a one-time tip if that works better for you.