We Should Celebrate

Come on. Everyone sees it. Sees what? she said. You share groceries. You have a favorite side of the couch. We’re roommates. Right.

The kitchen tap had been dripping for five weeks. Noah kept saying he’d fix it, Elena kept saying she’d call the landlord, and neither of them did anything about it. Now Elena stood at the counter cutting a lime while Noah sat at their small table, the one they’d found on the curb last spring, and the sound of the drip seemed to fill the entire apartment.

It’s not that far, she said. A plane ride, basically.

Right. Planes exist.

She turned to look at him. His face was doing that thing where he tried to appear neutral but his jaw tensed slightly, a tell she’d learned to read years ago.

Don’t make it weird, she said.

I’m not. I’m saying congratulations.

The lime fell into quarters under her knife. Outside, someone’s music drifted through the open window, bass heavy and indistinct. The apartment always felt smaller in summer, the heat pressing in through the walls, making everything stick—doors to frames, skin to vinyl chairs, words to throats.

She’d rehearsed this differently. In her head, Noah had been excited for her, maybe even jealous in that productive way that made him update his portfolio or apply for things. Instead he sat there pushing his thumbnail against the table’s chipped veneer, creating tiny half-moon indentations.

So when do you leave? he asked.

August. End of summer.

He nodded, pushed his hands into his pockets even though he was sitting down, which made him hunch forward awkwardly. The refrigerator hummed. The tap dripped. Someone outside laughed, sharp and sudden.

Elena brought him a beer without asking if he wanted one. Their fingers touched briefly when he took it. She sat down across from him and they drank in silence, the late afternoon light making everything look temporary, which she supposed it was. Had always been.

Three months, she thought. Twelve weeks. Simple math.

Seattle’s supposed to be nice, he said finally.

Yeah. Rains a lot though.

You hate rain.

I don’t hate it.

You literally refuse to leave the apartment when it rains.

That’s different. That’s Charlotte rain. Seattle rain is probably…I don’t know, part of the scenery.

He smiled then, just slightly, which made the corner of his eyes crease. She looked away, out the window where their neighbor was dragging a trash can to the curb, the wheels catching on every crack in the pavement.

Your parents know? he asked.

Not yet.

They’ll freak.

I know.

Your mom will cry.

I know.

She’ll make you take a Bible.

Elena laughed despite herself. She probably already has one picked out.

The beer was getting warm in her hands. She could feel him looking at her, carefully studying her face when he thought she wasn’t paying attention. She’d noticed it more lately, or maybe she was just letting herself notice it.

The marketing firm, the one downtown, wanted her too. Better benefits, comparable salary, ten-minute commute. Her mother would have been able to drop by for lunch. Noah could have walked over after work sometimes, like he did now, showing up with takeout from the place they liked, the one that knew their order.

But the Seattle job was with a bigger company. Would look good on a resume. Would mean she was going somewhere, becoming someone. Not just another Charlotte girl who never left, who settled for good enough, who let life happen to her instead of chasing it.

The sink dripped. One-Mississippi, two-Mississippi, three-Mississippi, drip.

I’m happy for you, Noah said, and she could tell he was trying to mean it.

Thanks.

We should celebrate. Get dinner or something.

Yeah, maybe.

He stood up, the chair scraping against the floor. For a moment she thought he might say something else, but he just walked to the sink and tried to tighten the faucet.

I’ll fix it before you go, he said.

You don’t have to.

I know.

But they both knew he would. He’d fix the drip and patch the hole in the wall behind her dresser and probably even paint over the water stain on the ceiling, and all these small repairs wouldn’t matter once she was gone but he’d do them anyway because that’s what Noah did.

The party wasn’t for her, technically. Jess’s birthday happened to fall two weeks before Elena’s departure, but somehow it had become about both things, if that was possible. People kept congratulating Elena and buying her drinks, and she kept accepting them, and now the room tilted slightly when she moved her head.

Noah stood by the kitchen island talking to someone from his work. She couldn’t hear what they were saying over the music, but she could see the way he held his beer, loose and low, completely comfortable in a way he never was at parties. He’d worn the blue shirt she’d bought him last Christmas. She wondered if that was on purpose.

Mark appeared at her elbow, already drunk, grinning. You two are ridiculous, he said.

What?

You and Noah. It’s like watching a nature documentary. David Attenborough should narrate your life.

Shut up.

Come on. Everyone sees it.

Sees what? she said.

You share groceries. You have a favorite side of the couch.

We’re roommates.

Right.

Elena took another drink. Across the room, Noah laughed at something, his head leaning back, and she felt it, almost like her own head was leaning back, too.

He’ll find another roommate, she said. Won’t take him long.

Mark raised his eyebrows. Sure. And you’re moving to Seattle for the career opportunity.

I am.

Nobody moves to Seattle in August. That’s when people leave Seattle.

The music changed to something slower, and people started pairing off. Someone pulled Noah toward the living room where people were dancing. He resisted, shaking his head, but then his eyes found Elena’s across the room and something tiny shifted in his expression.

She didn’t remember walking over, but suddenly they were facing each other while Jess shouted something about shots, and then his hand was on her waist and hers was on his shoulder and they were swaying to some song she’d heard a hundred times but couldn’t tell a soul what the name was.

This is a nice song, she said.

Yeah.

Okay.

Neither of them moved away. His thumb pressed against her hip bone through her dress. She could smell his deodorant, the beer on his breath, the laundry detergent they both used. Familiar things that shouldn’t have smelled unfamiliar, but they did.

The song ended. Another started. They kept dancing, barely moving really, just shifting weight from foot to foot while the party spun around them. Someone took a group selfie. Someone else whooped. Noah’s hand tightened slightly on her waist when the flash went off.

The music cut out abruptly because someone’s phone died. So they stepped apart like they’d been caught. The space between them felt both enormous and insufficient.

They ended up on the back porch, where the air was thick with humid cigarettes. Elena’s skin felt too tight.

You know, I really am happy for you, Noah said quietly.

Don’t start.

I’m not starting anything. I’m saying, maybe you think I’m lying.

The words came out angular, sharp-edged. She could feel the conversation moving toward something irreversible.

You think I’m just running away, she said. That’s what you want to say.

Aren’t you?

Better than standing still for the rest of my life.

He flinched like she’d slapped him. She immediately wanted to take it back, but also she didn’t want to bother feeling guilty. Who cares at this point, anyway.

That’s what you think I’m doing? Standing still?

No, I didn’t mean—

No, you did. You think I’m pathetic—

That’s not what I said.

And that I’m too chicken to leave, too—

Noah—

Forget it.

He went back inside, leaving her on the porch, alone save for the mosquitoes and the sound of distant traffic. Through the window, she could see him getting another beer, his movements stiff. Jess approached him, probably asking where Elena was, and he shrugged, gestured vaguely toward the door.

Elena stayed outside until her skin was covered in small, itching welts, punishment for something, most likely.

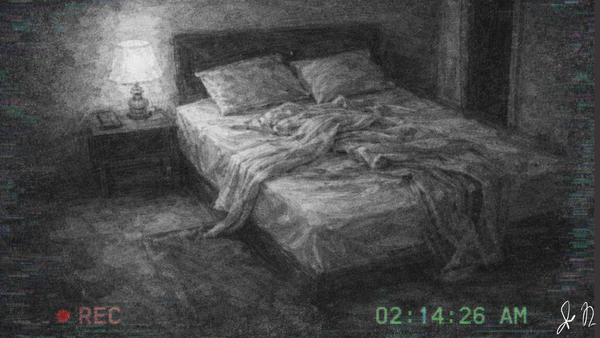

Boxes stacked against walls, furniture pushed into corners, shadow marks on the floor where things used to be. Elena and Noah sat on the futon, the only thing left in the living room, eating Chinese food straight from the containers. The fortune cookies remained unopened between them. Neither wanted to know what they said.

Noah had been quiet all day, helping her pack with stoic efficiency. He wrapped plates in newspaper, sorted her books by size, folded her clothes into boxes labeled BEDROOM and WINTER and MISC. Now they sat with their legs stretched out, not quite touching, while the air conditioning unit rattled through a vent that needed a new filter.

I don’t want you to go, he said suddenly.

Six words, each one a piece of glass hitting the floor. Elena set down her container carefully.

You don’t get to say that now.

I’ve wanted to say it.

She wouldn’t look at him. Outside, someone was dragging something heavy across pavement, the sound like static.

Noah, she said, and his name felt dangerous in her mouth.

I know I shouldn’t say it. I know. But I can’t let you leave without—

Without what? Making it harder?

It’s already hard.

She did look at him then. His face was doing something complicated, sort of collapsing and rebuilding in real time. She’d seen him cry exactly twice. Once when his grandmother died, once when they’d gotten too drunk sophomore year and he’d told her about how his father left him and his sisters. But this was different.

I’m scared, Noah, she said, and the admission surprised her.

Of what?

Of doing what I want.

The air conditioner rattled again.

Noah shifted closer, his knee touching hers. You know I wouldn’t—

I know. That’s what makes it worse.

He reached over and touched her face, his thumb against her cheekbone, and she leaned into it without meaning to. They stayed like that for a moment, suspended. And then they were hugging, which they almost never did. His hand was in her hair, her fingers gripping his shirt, both of them trying to compress years into seconds.

When they pulled apart, she was crying. He might have been too. It was hard to tell in the dim light.

The truck’s downstairs, she said.

Right.

He tried to smile but it didn’t work. They sat there for another minute, their foreheads touching, breathing the same air.

Then she stood up. He stood up. They looked at each other across the strange, empty room that had been theirs, that was nobody’s now.

I love you, he said. I hope you know that.

She wanted to say it back. She could feel the words forming in her throat. But saying it would make leaving impossible, and she’d already paid the deposit and shipped half her things and told everyone she was going.

Instead she hugged him again, quick and fierce, and then grabbed her keys from the counter.

Elena, he said, but she was already at the door.

Take care of yourself, she said, and then she was gone, down the stairs and into the truck where the driver was waiting, scrolling through his phone.

As they pulled away, she could see Noah’s silhouette in the window, backlit and still. She watched until they turned the corner, and then she faced forward and cried quietly.

The highway stretched ahead, dark and certain. This time next week she’d be in Seattle. She’d start becoming whoever she was supposed to become. But right now she was just a woman in a truck, driving away from the only person who’d ever really known her, and that knowledge would be glass shards in her chest, at least for a while.

Her phone buzzed. A text from Noah. The sink is fixed.

She turned the phone face down and kept going.

Jon Negroni is a Puerto Rican author based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He’s published two books, as well as short stories for IHRAM Press, The Fairy Tale Magazine, and more.

Author’s Note

I’ve been asked a few times what my “paradigm shift” was as a fiction writer, and the answer varies depending on my mood. But if I had to pinpoint a moment in time when all bets were off in terms of my more contemporary obsession with the concept of “never-lovers” (people who want to be together but are in a seemingly never-ending battle against fate, A.K.A the author dictating the story A.K.A real life) it would have to be the first time I read Sally Rooney’s Normal People in 2018.

In many non-subtle ways, “We Should Celebrate” is my tiny nod to Rooney’s style and sensibilities, particularly as I’m finally making my way through her latest book, Intermezzo (side note: the international edition cover design I got in Iceland is an absolute upgrade if you can shop it). Obviously, I can’t just imitate Rooney’s work and expect that to be a functional short story worth anyone’s time, so I have my own voice creeping throughout, much of it intertwined with my parallel and seemingly inverse obsession with the wit-poise of Emily Henry, particularly in how she shapes characters using accessible archetypes with sandy edges. After finishing up Beach Read and Funny Story over the summer (I much preferred the later, for the record), it was likely no surprise to Natalia Emmons (the editor of this piece) that I would be finishing my favorite season of the year with this quirky hybrid of two wildly different styles.

Matter fact, Natalia’s first question to me during the line edit was whether or not this story is based on anything real. “Charlotte to Seattle feels pretty specific” she emailed with the double-eye emojis. And the answer is no, I’ve never had a “thing” with a roommate. I’ve also never lived in Charlotte or Seattle. But Lynchburg (where I grew up) and San Francisco (where I moved to in 2014) would be far too on the nose and a bit too close to home, so to speak, whereas Charlotte and Seattle represent two places I’ve been to very often that also feel so grounded in a split picture of the U.S. After all, they’re completely different places and representative examples of modern urban life, while also fondly regarded for their own reasons. That said, there is the pesky weather (of which I don’t give Charlotte enough grief considering its humidity).

Anyway, the structure of this piece is a bit different for me, so please indulge the lengthy but hopefully substantive explanation. I typically try to do these stories either as one scene or about six for the longer ones. After last week’s more epic tale and I believe our longest yet, I knew I wanted to do a shorter one right after. But one scene for a story like this wouldn’t quite work or feel satisfying, at least to me. So for perhaps the first time in years, I did a three-scene short story. And as a first, I structured the scenes to follow a classic three-act movie structure. That means we have the setup, the confrontation, and the resolution. Easier said than done, by the way.

Screenplays follow a three-act structure because they have room to build arcs over hours or hundreds of pages. Short stories, on the other hand, thrive on compression, ambiguity, and implication. For movies, Act I is typically about 25% of the runtime, Act II is about 50%, and Act III is another 25%. So if you try to proportion that out, the Act 1 of your short story can swallow a huge chunk of the piece before anything even happens. This is why many writing gurus advise the overwhelming bulk of your short story to be in media res, or taking place during Act II, with Act I and Act III being hinted at through gestures, flashbacks, and so on.

Like many other writers, however, I developed my own style that better matches my personality of storytelling. But part of growing as an author involves experimentation and risk-taking. Just look at Rooney, the inspiration of this piece. I’ve read each of her books since Normal People, and she constantly builds upon her form and function, constantly takes bigger and bigger swings. Fortunately for you readers and subscribers, the failed experiments I write never make it to page.

And yes, the prose here is also a grand experiment. To evoke both Sally Rooney and Emily Henry, I’m choosing language that is spare but also intimate, a beautiful paradox that can easily self destruct without proper editing. The POV is close third person with deep interiority, but at times it can almost read as third person omniscient in how it slides between the consciousness of two characters. The dialogue absolutely has to be understated, but it also has to be emotionally piercing. And I’m taking special care to reveal ordinary settings and small gestures as a way to paint the atmosphere with restraint and loaded subtext.

Hence the paradigm shift I mentioned earlier. See, I used to despise writing like this because I frankly didn’t understand the point of these contradictions and how they could cohesively form a compelling story with poetic resonance. But by removing the melodrama (along with all the quotation marks and other formatting), you make the reader work harder to feel something. Thus, that feeling they fall into is no longer fleeting or cheap or split between them and a crowd being pleased.

Because everyone already knows how “love stories” go. Two people are either going to get together or they’re not. To find that more specific, untold itch, I had to dig deep. What if they were already in a love story and just didn’t realize it until the end? Skip the montage, the wedding, the “oh no I have feelings for them now that they’re dating someone else” reveal. And just get to the part where time runs out and let that burn in the chest of every reader who knows at least some form of that regret. I should’ve fixed the sink sooner. I should have told them how I felt sooner.

Thank you for reading Cetera. Subscribe for free to receive new stories every week, right in your inbox. And if you have a few extra seconds, please consider sharing this story with a friend who might like it.